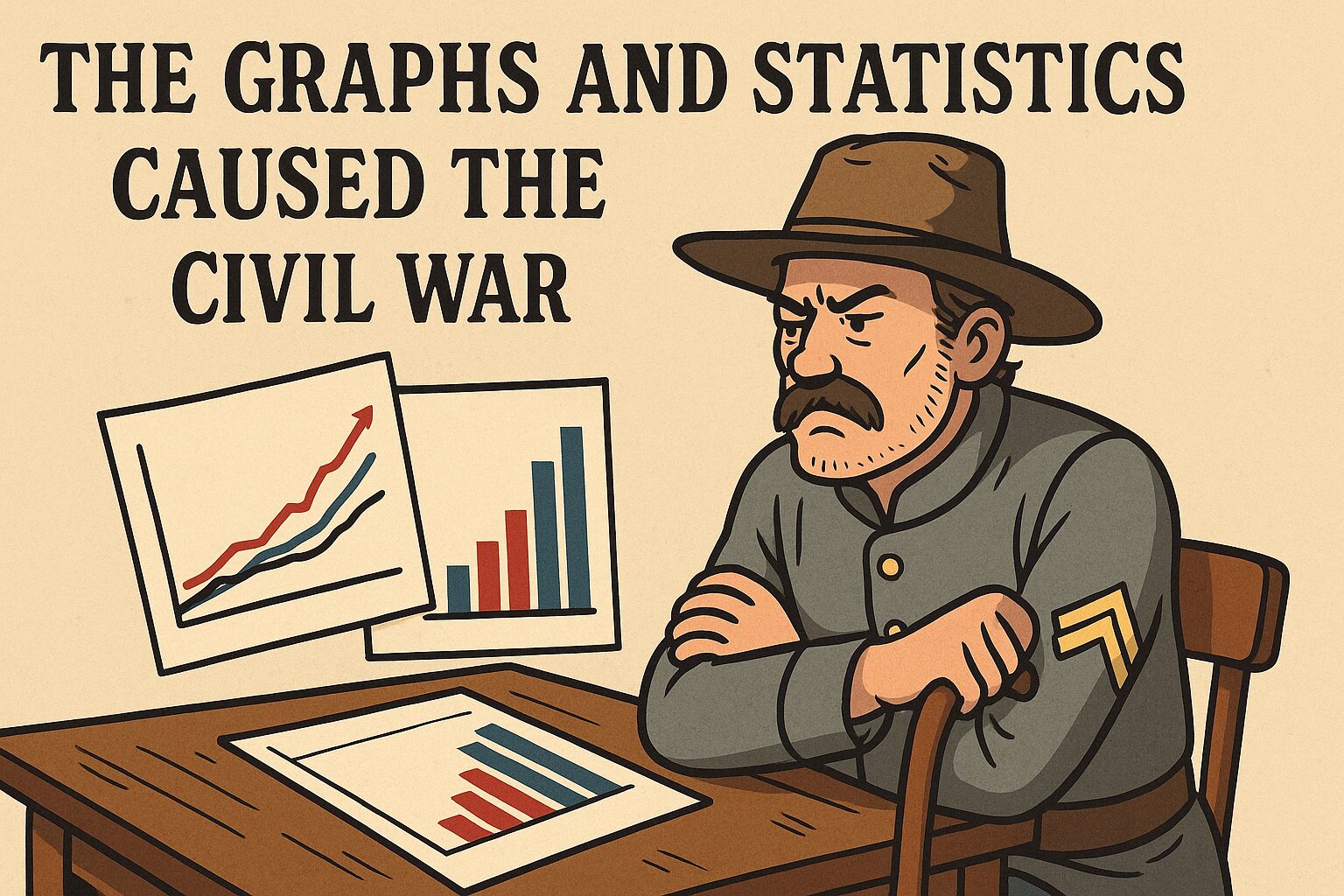

We often explain the Civil War as a conflict over slavery, and while that’s true, the deeper constitutional rupture came when the South recognized it had lost control over all three branches of the federal government. The numbers—and the graphs—tell the story.

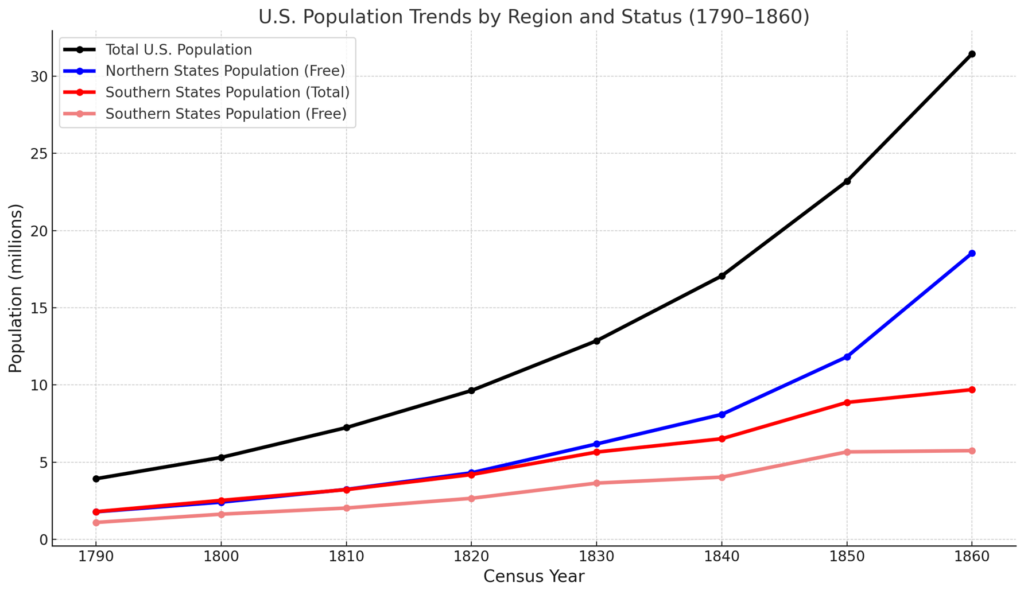

Below is a graph of the populations for both the Northern and Southern states. For this graph, I have assumed that a Southern state is one where slavery was legal as of 1860, when the Civil War broke out. The South is clearly a minority population relative to the US population, yet the South controlled much of the federal government throughout the antebellum years as we will see in later graphs.

Graph 1. US Population by region. The curves for the Southern states show total population (free citizens plus enslaved ones) and free population.

The Constitution Tried to Protect the South

At the Founding, the South was a powerful minority. Though smaller in population, its wealth, unity, and agricultural exports gave it an outsized influence. The Constitution was, in many ways, a grand compromise: a structure that allowed slavery to exist under federal protection, even as the ideals of liberty were written in parchment.

In fact, the Founders did not include the word “slavery” in our Founding document out of fear of “tarnishing” it.

The framers knew they were creating a system that allowed for moral disagreement, but they also embedded protections for minority interests—especially in the Senate, where equal state representation gave slaveholding states a long-standing veto.

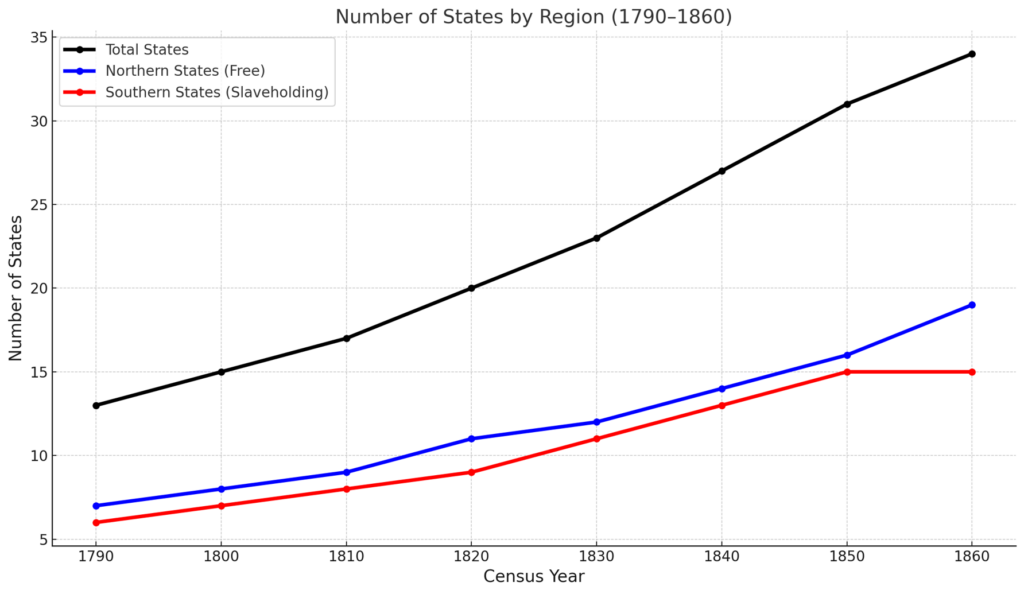

Graph 2. Count of Southern states vs Northern states. The Constitution and the compromises in 1820 and 1850 concerning admitting new states as free or slave maintained a balance in the number of states to each region.

And for decades, it worked—by “worked,” I mean that it postponed the moral reckoning. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 were political duct tape meant to hold together a nation morally at odds with itself. These compromises were enabling the nation to work through the moral issues surrounding slavery—for good or for bad.

But history bends, as it always does. And in the US, that bend has been towards the good.

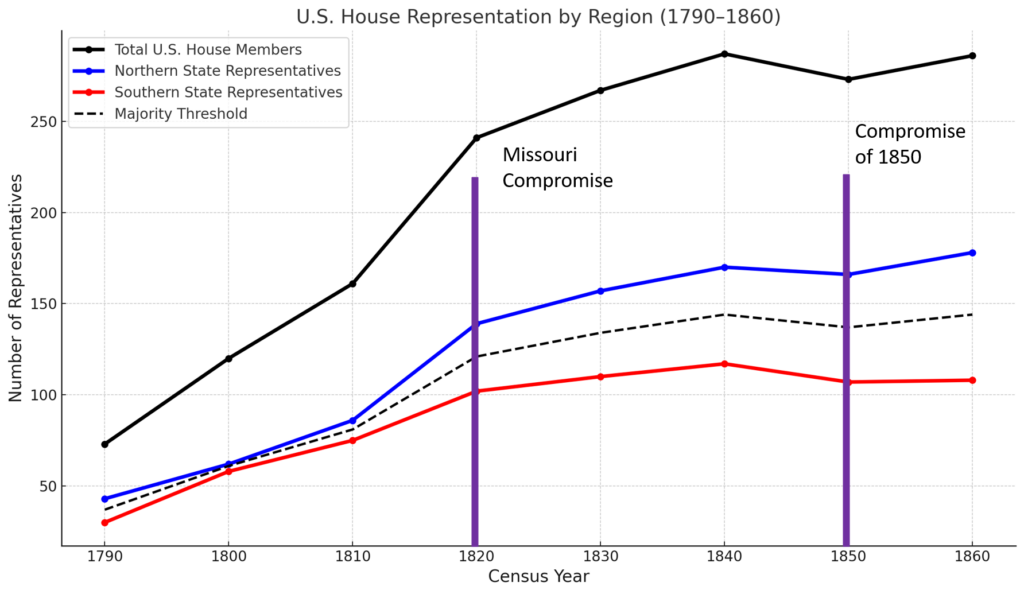

The South Was Losing the Numbers Game

For most of the early republic, the South held its own politically—even while in the minority—thanks to a set of structural advantages embedded in the Constitution. Chief among them was the Three-Fifths Compromise, which allowed slaveholding states to count three out of every five enslaved people toward their population totals for purposes of House representation and Electoral College votes. This gave the South disproportionate power in Congress and the presidency.

But by the mid-19th century, the arithmetic was turning against them.

1. Population Growth Favored the North

As the population graphs show, Northern states experienced explosive demographic growth between 1790 and 1860. Waves of European immigration, urbanization, and industrialization drew millions to cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. In contrast, the South remained rural and agriculturally anchored, its economy dependent on enslaved labor and cotton exports.

By 1860, the North held a clear majority of the national population—even without counting enslaved people. More people meant more House seats. And more House seats meant more power to control national legislation. The South, by contrast, was stuck with fewer people and fewer votes—and their portion of the House delegation was shrinking with each census.

Graph 3. Representation by region in the House. Note the effects of compromise to “appease” the South and assist in maintaining the votes.

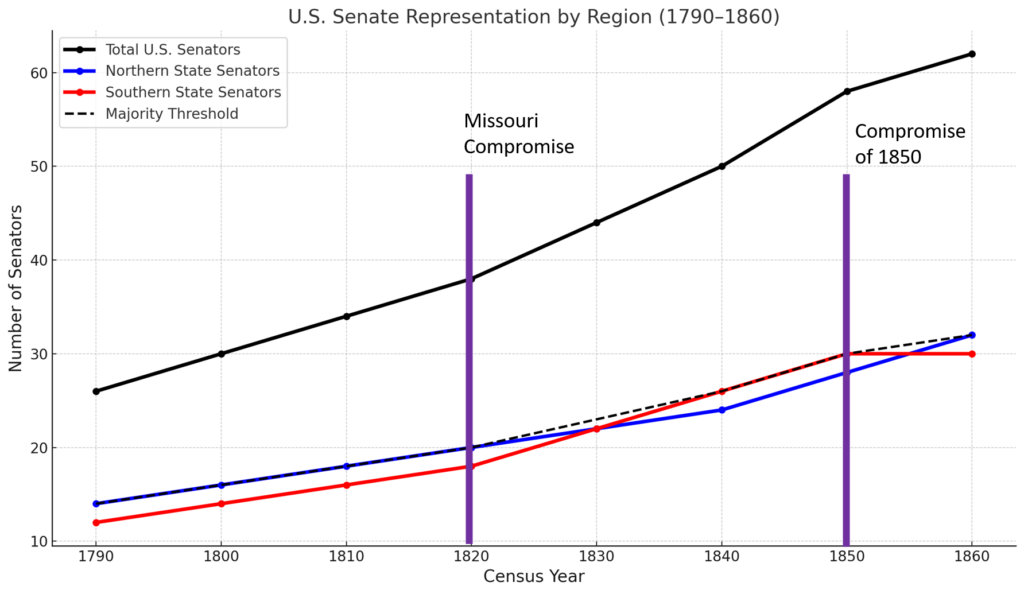

2. Senate Balance Couldn’t Hold Forever

In the Senate, slave and free states had been kept roughly balanced for decades through a series of political compromises. Each time a free state was added, a slave state was paired with it—Missouri and Maine, Arkansas and Michigan, Florida and Iowa, Texas and Wisconsin.

But that strategy was inherently unsustainable. The West—particularly the upper Midwest—was filling with settlers from Northern states who brought with them anti-slavery values and free labor ideals. New free states were inevitable. New slave states were not. The Compromise of 1850 tried to delay the crisis, but by 1860 the North had a growing advantage in the Senate, and every indication was that the trend would continue.

Graph 4. The control over the Senate and the narrow margins that compromise agreements protected for the South until the 1860 election.

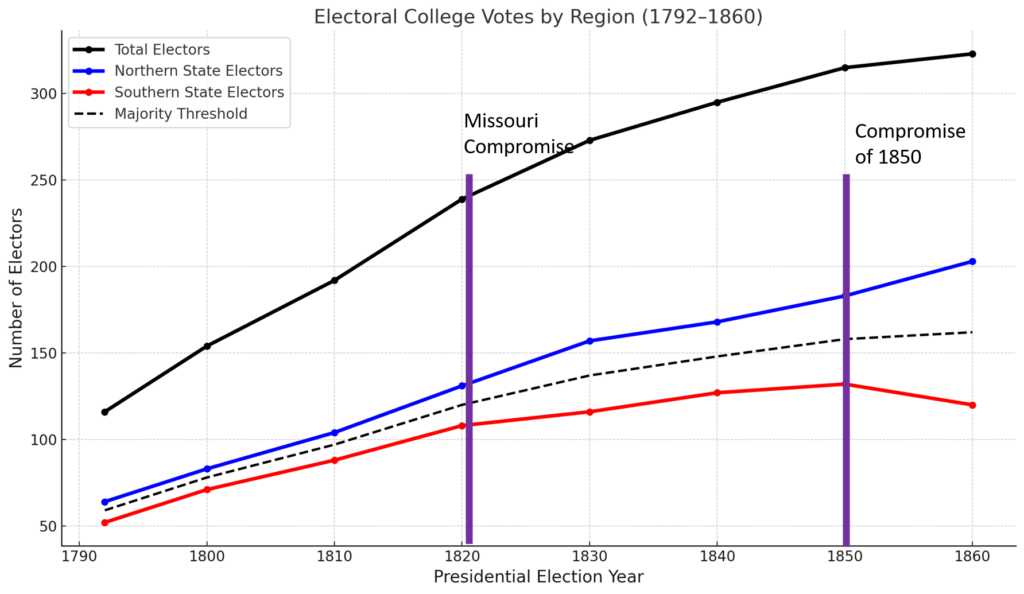

3. The Electoral College Was Slipping Away

Our Electoral College graphs show the cumulative tipping point: by 1860, the North had amassed a dominant number of electors. Lincoln’s election—with zero Southern electoral votes—proved that the South could no longer veto national leadership. They had become politically isolated in the very system they once dominated.

Graph 5. The Electoral College, which determined control over the Executive Branch, was further slipping from the grasp of the South.

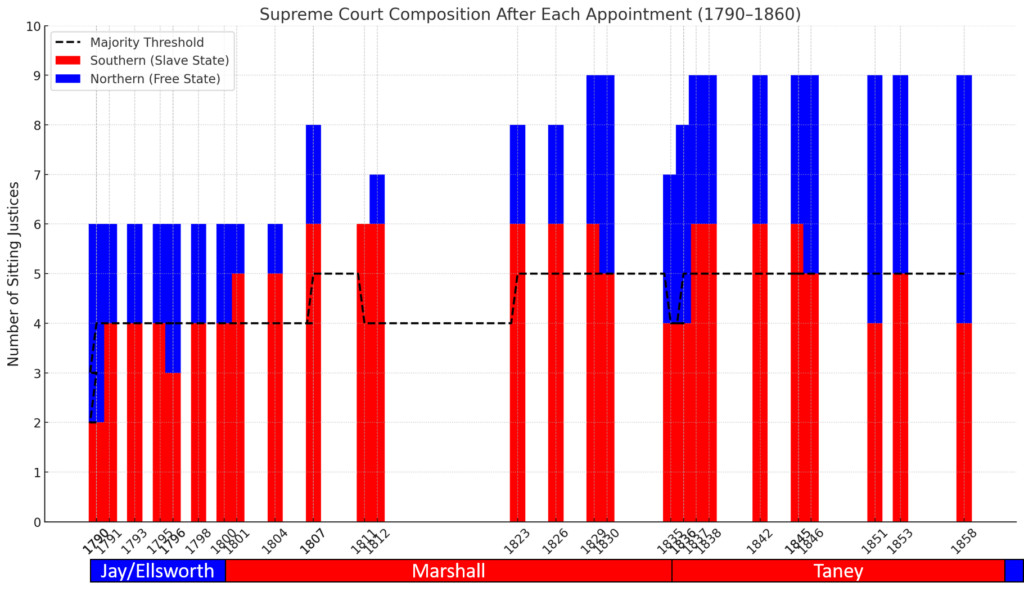

4. The Supreme Court Was a Temporary Stronghold

Yes, the Dred Scott decision in 1857 represented a Southern victory in the judiciary. But that was a last gasp, not a sustainable base of power. As the graph below on judicial appointments shows, the South had begun to lose ground even on the Supreme Court. Lincoln’s presidency guaranteed that future appointments would tilt the bench toward the free states. The judiciary, like the other branches, was slipping out of Southern hands.

Graph 6. The Supreme Court Justices and their region of origin. The bottom of the graph also shows the name and origin of the Chief Justice, which shows the dominance of the South in leading the Court. Chief Justice Taney ruled on the Dred Scott Case, and by 1860, he had served nearly 24 years on the court.

From Dominance to Defeat

The loss of control for the three branches was not just a political change—it was an existential loss. The South had long relied on federal power to protect its interests, especially slavery. But by 1860, every structural advantage was unraveling. The data tells the story:

- They were outnumbered.

- They were outvoted.

- They were outmaneuvered.

Secession was not just about slavery. It was about losing the ability to defend slavery through democratic means.

The South didn’t rebel because the system failed them. They rebelled because the system was no longer under their control—and because the moral tide was no longer willing to bend to their cause.

And then came the tipping point.

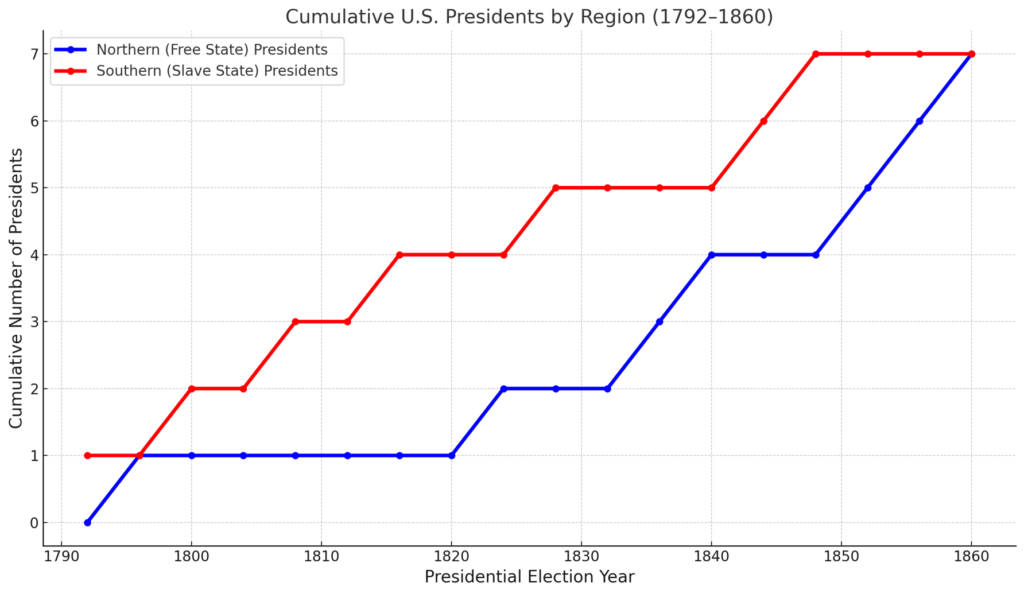

Graph 7. The South had nearly controlled the Executive Branch from the start of the US federal government. Except for John Adams, the first run of Presidents were Southerners, Virginians nonetheless. The election of Lincoln for the first time brought parity in the number of presidents elected from each region—a tipping point.

Lincoln’s Election: The Constitutional Collapse

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 was the political signal that the South had lost all three branches of government:

- The Presidency: Lincoln won without carrying a single Southern state.

- Congress: The North controlled the House decisively and was gaining in the Senate.

- The Supreme Court: Though still staffed with some Southern-leaning justices, the South could no longer count on holding future appointments.

The Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision had tried to cement slavery’s legitimacy. But instead of securing slavery, it radicalized the North and split the Democratic Party—paving the way for Republican ascendancy.

By 1860, the game was up. And so the South did what any child does when they realize they can’t win anymore under the rules: they took their ball and went home.

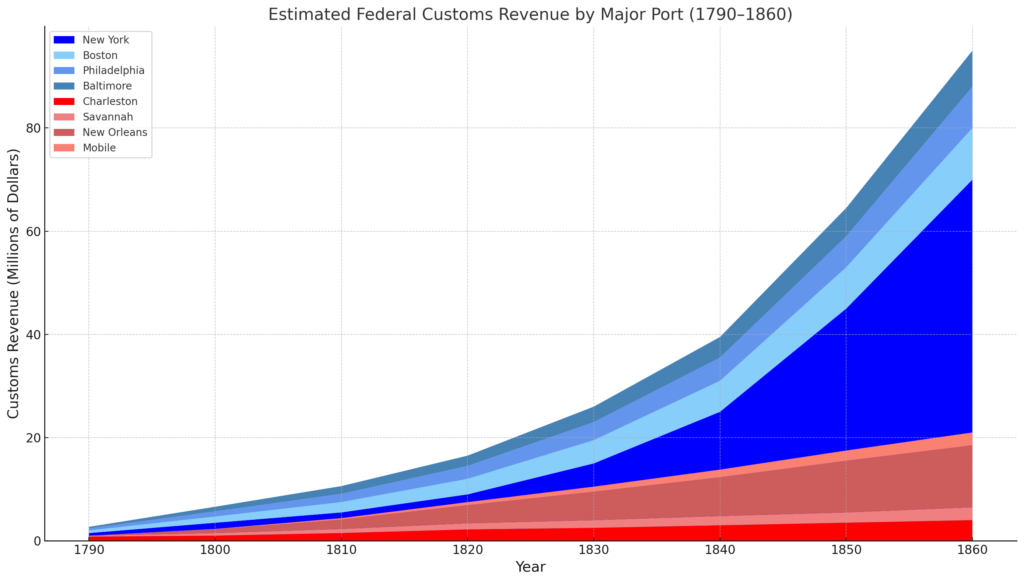

But Did the South Pay the Price?

Contrary to Lost Cause mythology, the South wasn’t overtaxed. The next graph show that Northern states paid the lion’s share of federal taxes through tariffs and customs duties. The effective per capita tax burden was consistently higher in the North.

Still, Southern leaders felt encircled—culturally, politically, and economically. And in some ways, they were right: the Constitution had protected them for decades, but it was no longer enough to protect a minority interest built on an immoral institution.

Graph 8. The primary source of federal revenue from 1790 to 1860 was through tariffs collected by customs at ports. This stacked line graph shows estimated federal customs revenue by major U.S. ports. The blue shades depict Northern ports while the red shades depict Southern. New York dominated customs revenue, especially after 1830. Southern ports contributed modestly in comparison though New Orleans grew significantly after 1830.

The Constitution Held, But Morality Moved

The secession of the Southern states was not just a rebellion against the Union. It was a rebellion against democratic outcomes. The Constitution gave the South a seat at the table. But when the South lost the votes, they tried to overturn the table itself.

And yet, the fact that the Union survived—even at the cost of war—is evidence that the Constitution worked not because it froze power, but because it allowed the nation to adapt.

The South didn’t lose because they were misunderstood. They lost because history progressed, and they refused to go with it.

Disclaimer: ChatGPT generated and edited portions of this blog post.

Enjoying reading this David