When the Founders envisioned the U.S. Supreme Court in 1787, they likely imagined a bench of wise, grounded citizens—people deeply acquainted with the law, yes, but also embedded in the country they served. For much of its early history, the Court fulfilled that ideal as a body of justices drawn from every corner of the republic, including planters, politicians, military veterans, and even a few without formal legal education.

Today, however, the Court looks very different. It has become a judicial elite, a kind of modern priesthood where only the most rigorously trained in the constitutional catechism are allowed to enter. If that sounds dramatic, let the data speak for itself.

Figure 1. This stacked bar chart shows the estimated backgrounds of Supreme Court Justices divided by four historical periods.

The figure above illustrates how the backgrounds of Supreme Court Justices have changed over the years. To date, we have had 120 justices. The periods shown are:

- 1789–1865 (Founding to Civil War)

- 1866–1932 (Reconstruction to New Deal)

- 1933–1968 (New Deal to Civil Rights)

- 1969–Present (Modern Era)

Some key trends to note in this data are:

- Lawyers dominated across all periods.

- Politicians and Planters/Farmers were prominent early on but diminished over time.

- Academics rose significantly in the 20th and 21st centuries.

- Military experience was more common in earlier periods.

- Business backgrounds remained relatively rare throughout.

The Shrinking Path to the Bench

One graph shows the overwhelming majority of Supreme Court justices have always had some legal training. But if we refine that to count only those who actively practiced law, the number becomes smaller—especially in recent decades, where legal practice has given way to academic and judicial credentialing.

Figure 2. This chart shows the estimated number of Supreme Court Justices by type of legal training across the four historical periods.

In Fig. 2, the training type follows the following categorizations.

- Constitutional Law Training: Justices who studied constitutional law as a distinct academic discipline (mostly 20th century and later).

- General Legal Training Only: Justices trained in law (e.g., via apprenticeships, law schools) without a specific focus on constitutional law.

- General Legal Training Only: Justices trained in law (e.g., via apprenticeships, law schools) without a specific focus on constitutional law.

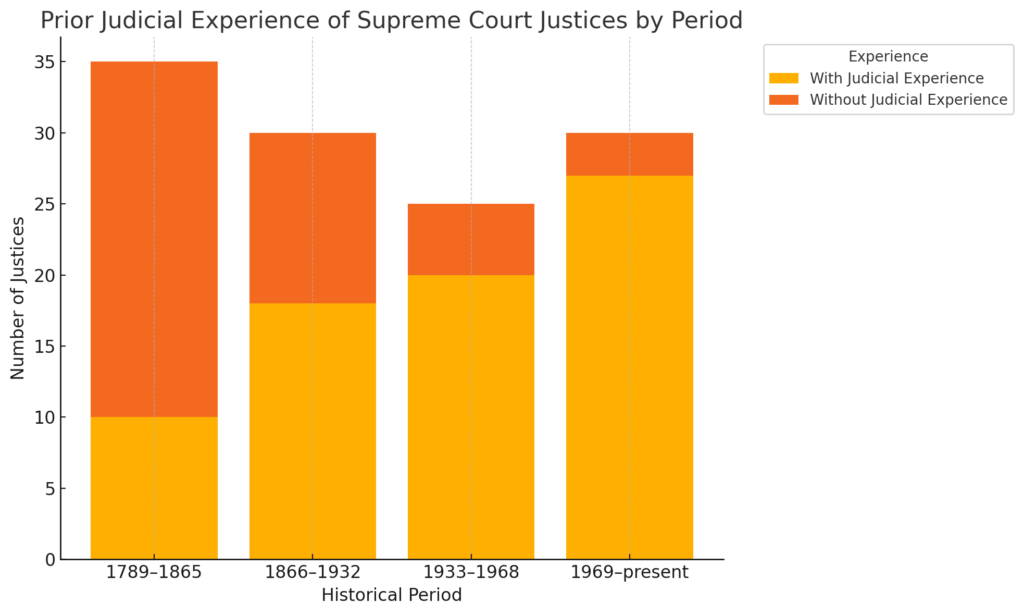

Figure 3 breaks this down by prior experience as a judge. In the early republic (1789–1865), it wasn’t uncommon for justices to have no previous judicial experience. Many were state legislators or diplomats who read law as apprentices. Only 10 out of 35 had prior judicial experience before joining the high court.

Fast forward to today, and the story flips: 27 of the last 30 justices had already served as federal judges before nomination. Not only must one be a lawyer, one must already be a judge—preferably a federal appellate judge. The path is no longer wide and varied. It is narrow, formalized, and insular.

Figure 3. Again, using the four historical periods, this stacked bar chart shows how many U.S. Supreme Court Justices had prior judicial experience before joining the Court.

The story of Fig. 3 is that the early justices did not have prior judicial experience—many were statesmen or lawyers. Then after the Civil War, judicial experience become more common but was not universal. Then, a strong shift toward appointing experienced judges from the New Deal to the Civil Rights era. Finally, in the modern era, nearly all justices have served on lower courts before joining the Supreme Court bench, reflecting increasing professionalization—some might say indoctrination into the priesthood—of the judiciary.

Constitutional Law: From Common Sense to Canon Law

Perhaps more striking is the shift in legal education. Constitutional law wasn’t even a formal academic field in the Founders’ time. Yet today, nearly every justice from the modern era has been educated in it, often at the highest levels. Recall that Fig. 2 shows the steep rise of justices with specific constitutional law training, compared to those with only general legal education.

It’s not just about knowing the law anymore; it’s about interpreting the Constitution within the accepted frameworks of legal orthodoxy. That makes for intellectual consistency, but it also breeds theological rigidity. The sacred texts (i.e., the Constitution and its case law) are now interpreted by high priests of jurisprudence, not citizen-philosophers.

We the Justices?

Here’s the deeper concern. The early justices were part of “We the People” in both background and experience. Today’s justices increasingly resemble a cloistered order, trained by their predecessors, clerking for past justices, and living within a closed intellectual loop. The Court is more internally coherent than ever before, but perhaps also more detached.

Their social world is Washington, D.C.—not Kansas, not Mississippi, not Colorado—suggesting that the Court now orbits more around the capital’s elite legal sphere than the everyday lives of the people it serves.

That detachment matters. The law does not interpret itself; it is interpreted through the lived experience of the interpreters. When that experience is so uniformly elite, even brilliant minds can fall prey to a collective blind spot.

Figure 4. Have “We, the Justices” become more important than “We, the People”?

The Risks of a Judicial Priesthood

We should be cautious not to overstate the metaphor: the Court is not a literal priesthood. But it bears the hallmarks:

- Doctrine: Originalism, textualism, the living Constitution—each its own theology.

- Vestments: Robes, ceremonies, sacred oral arguments.

- Apostolic succession: Clerkships and mentorships forming an unbroken line of doctrinal lineage.

- Sanctuary: A marble palace separate from the rest of the government, immune from elections.

This evolution may provide stability and intellectual rigor. But it comes at the cost of democratic diversity. The Court risks becoming less a guardian of “We the People” and more a steward of “We the Justices.”

Where Do We Go From Here?

We don’t need to tear down the temple. But we should broaden the doors. Judicial excellence need not be synonymous with elite homogeneity. There is room for a justice who was a mayor, a trial lawyer, or a public school teacher. The Court has room for a voice shaped more by jury trials than by law review articles.

And maybe—just maybe—it’s time to rethink the geography of justice itself. The Supreme Court doesn’t have to be walled off in the marble sanctum of Washington, D.C. What if it met in St. Louis? Or Denver? Or rotated among different cities, like a constitutional circuit rider? Even symbolic decentralization could restore some sense that the Court belongs to We the People, not just to the Beltway elite.

The Constitution belongs to all of us. Perhaps the Court should, too.

Postscript & Disclaimer:

This post was inspired by a lively discussion at our May 17 “Donuts for Democracy” gathering. Special thanks to my colleague Andy Andrews, who raised the question that sparked it all: Has the U.S. Supreme Court become more a body of legal clerics than citizen judges? What began as a tongue-in-cheek observation evolved into a serious inquiry—supported by data, history, and a healthy dose of satire.

Portions of this post were also written with the assistance of ChatGPT. As always, final interpretations and opinions are my own.

Timely news from the Department of Justice: https://fxn.ws/3Z7jW8J.

In a development that ironically affirms the central argument of this post, the Department of Justice has just announced it will no longer recognize the American Bar Association’s ratings when reviewing judicial nominees. Far from undermining the idea of a legal “priesthood,” this move suggests that Trump’s DOJ sees the ABA as a high cleric within it—an institution with undue authority to confer blessings or issue condemnations from behind the velvet curtain of elite consensus.

This is not a rejection of theocratic drift in the judiciary—it is a counter-reformation.

If the ABA has functioned as an ecclesiastical body within the legal order, offering its imprimatur only to those who pass muster in temperament, training, and ideology, then the DOJ’s decision represents a deliberate break from that hierarchy. What we’re witnessing is not a return to democratic accountability, but a reshuffling of who gets to wear the robes and swing the incense. It is an acknowledgment that a priesthood exists—followed immediately by a hostile takeover.

In that sense, the move validates this blog’s broader thesis: that our judicial institutions have become more insular, credentialed, and self-replicating over time. What’s new is that the partisan actors aren’t seeking to restore balance—they’re appointing their own high priests.

As ever, the robe remains. Only the vestments change.