Executive Summary

This whitepaper advocates for integrating Approval Voting (AV) into closed primary systems as a necessary reform to improve representativeness, reduce extremism, and restore faith in democratic outcomes. While closed primaries may serve a valid function in preserving party integrity, their current use of first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting methods leads to the selection of nominees who do not command majority support—even within their own party.

Drawing on the political philosophy of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, and referencing Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem and Condorcet’s criterion, this paper argues that while no perfect voting system exists, we can still adopt better systems. Modern tools like AV are not only feasible to implement but are already used in non-political settings where group decision-making must be fair, rational, and majority-oriented.

By adopting majority-sensitive voting within closed primaries, we preserve the rights of parties to choose their nominees while ensuring that such nominees reflect the broader will of party members—not just the most mobilized factions.

Introduction: The Electoral Moment

The American public increasingly distrusts both major parties. At the same time, we face no structural path to avoid their grip. While many voters express dissatisfaction, the actual mechanisms of political selection—especially party primaries—are built on outdated assumptions and winner-take-all systems. Our goal is not to challenge closed primaries per se, but to equip them with modern mechanisms of majority detection.

The Value—and Risk—of Closed Primaries

Closed primaries exist for a reason. They allow political parties to maintain coherence, prevent partisan sabotage from opposing voters, and ensure that candidates selected to represent a party genuinely reflect the party’s values.

But there’s a flip side.

In a hyper-partisan age, the voters most likely to participate in closed primaries are also the most ideologically extreme. They feel warmly toward their own side and view the opposition with suspicion or outright hostility. That emotional fuel drives more polarizing candidate choices and more punishing general election rhetoric.

And because turnout in primaries is often low—and closed primaries restrict participation even further—the candidates selected often reflect the preferences of a minority within the party.

To honor the purpose of closed primaries while improving their function, we must reform the voting method used within them.

The Constitutional Premise: Madison and Hamilton

James Madison, the architect of faction management, warned against the danger of minority rule within majorities. He believed in refining public opinion through representative structures. Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s most forward-thinking institutionalist, prized executive clarity and electoral legitimacy.

Both would likely view modern party primaries with suspicion:

- Madison would fear factional capture.

- Hamilton would worry about instability from unrepresentative nominees.

While neither man knew AV or RCV by name, both supported institutional innovations that promoted compromise, balance, and majority consent. These principles align squarely with the logic of modern majority-sensitive voting systems.

Arrow’s Criteria and the Impossibility Theorem

Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow formalized a challenge now known as Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. It shows that no rank-based voting system can simultaneously satisfy all five fairness conditions when there are three or more candidates:

- Non-Dictatorship – No single voter should always determine the outcome.

- Example: A system where one voter’s preference always wins, regardless of others’ input.

- Unanimity (Pareto Efficiency) – If all voters prefer A over B, then B should not win.

- Example: If everyone ranks A above B, B cannot be the winner.

- Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) – The relative ranking of A vs. B should not be affected by introducing or removing C.

- Example: Adding a minor candidate changes the winner from A to B.

- Transitivity (Consistency) – If A beats B and B beats C, then A should beat C.

- Example: If voters prefer A to B and B to C, it should follow that A beats C.

- Universal Domain – The system must work for any set of preferences.

- Example: All possible voter rankings are valid inputs.

Arrow’s theorem does not render reform useless. Instead, it clarifies that trade-offs are inevitable. Every system must prioritize which criteria it preserves.

The Condorcet Perspective

A Condorcet winner is a candidate who would defeat every other candidate in head-to-head matchups. Not all voting systems guarantee that such a candidate will win:

- FPTP often fails the Condorcet test.

- AV and RCV improve the odds of a Condorcet winner but may still fall short depending on preferences.

Still, both AV and RCV outperform FPTP in surfacing broadly acceptable candidates.

How AV and RCV Work

- Approval Voting: Voters may vote for as many candidates as they find acceptable. The candidate with the most approvals wins. Simple. Transparent. Easy to count.

- Ranked Choice Voting (RCV): Voters rank candidates in order of preference. If no one gets a majority, the lowest-ranked candidate is eliminated and votes are redistributed until a majority winner emerges.

Both systems reduce vote-splitting, elevate consensus candidates, and eliminate the spoiler effect. AV is often favored for its simplicity and lower administrative burden.

A Vivid Illustration: Six Voting Methods, Six Winners

Consider this fictional example of six groups of voters, each ranking five candidates (A, B, C, D, E). The table below shows the preferences of each voting bloc:

| # of Voters | 36 | 24 | 20 | 18 | 8 | 4 |

| 1st Choice | A | B | C | D | E | E |

| 2nd Choice | D | E | B | C | B | C |

| 3rd Choice | E | D | E | E | D | D |

| 4th Choice | C | C | D | B | C | B |

| 5th Choice | B | A | A | A | A | A |

Depending on which system is used, the outcome differs:

- Simple Majority: No candidate has >50% of first-choice votes.

- First-Past-the-Post: A wins (36% of votes).

- Runoff System: B wins.

- Alternative Vote (RCV): C wins.

- Borda Count: D wins.

- Condorcet Method: E wins.

This illustrates Arrow’s point: no system is perfect. But if your goal is majority legitimacy, AV and RCV outperform FPTP by large margins.

Modern Institutional Usage

While AV and RCV are still rare in political elections, they have become mainstays in major institutions:

- Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers (IEEE): Uses AV for board elections.

- Mathematical Association of America (MAA): Employs AV.

- American Statistical Association (ASA): Uses RCV.

- ACM (Association for Computing Machinery): Employs AV.

- Faculty Senates, student governments, engineering societies, and awards committees often use AV or RCV to reflect nuanced support.

These organizations adopted majority-sensitive methods not because of politics, but because they work better. They reflect the consensus of sophisticated groups that rely on decision accuracy.

Historical Context: Why FPTP Endured

FPTP was not enshrined in the Constitution—it was a practical default inherited from British common law. Its advantages in the 18th century were clarity and simplicity: votes could be counted quickly, even by candlelight. But this simplicity has a modern cost: misrepresentation in crowded fields. With the rise of primaries, FPTP increasingly delivers plurality winners who lack legitimacy, especially when multiple candidates split the moderate vote. Only now—armed with computers and digital tallying—can we feasibly implement methods like AV and RCV at scale with relative ease.

Majority Rule and the Madisonian Standard

James Madison warned of the dangers of factions and minority rule. He believed that the cure for faction was not censorship or suppression, but institutional structures that force competing interests to compromise. A voting method that routinely allows 30% of a party to override the remaining 70% is not Madisonian—it’s factional.

In Federalist No. 10, Madison argued that republican government must “refine and enlarge the public views by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens.” If we are to honor that vision, our voting system must reward candidates who can appeal to the full body of citizens—not just the loudest third.

Philosophical Foundations of Representative Government

What is a vote? A token of loyalty? A signal of preference? A strategy? In FPTP, it’s often all three—and not in a good way. Voters are regularly forced to abandon their true favorite for a “lesser evil.” Approval Voting and Ranked Choice Voting offer a way out of this trap by allowing voters to express a broader range of preferences without fear of wasting their vote.

These systems honor the complexity of voter sentiment. They enable voters to say: “I like Candidate A the most, but I could live with B. Please don’t stick me with C.” This layered expression aligns more closely with the deliberative ideals of the Founders.

Primaries, Polarization, and the Role of Voting Systems

To fully grasp the urgency of reforming how we conduct political primaries, one must reckon with the steadily worsening problem of negative partisanship—a phenomenon where voters are motivated less by support for their own party and more by antipathy toward the other. This form of tribalism distorts both democratic accountability and electoral representation. Fortunately, a careful examination of voting behavior data, when combined with thoughtful primary design, points toward a structural fix: majority-sensitive voting methods like Approval Voting (AV) and Ranked Choice Voting (RCV).

Who Votes in Primaries? A Skewed Subset

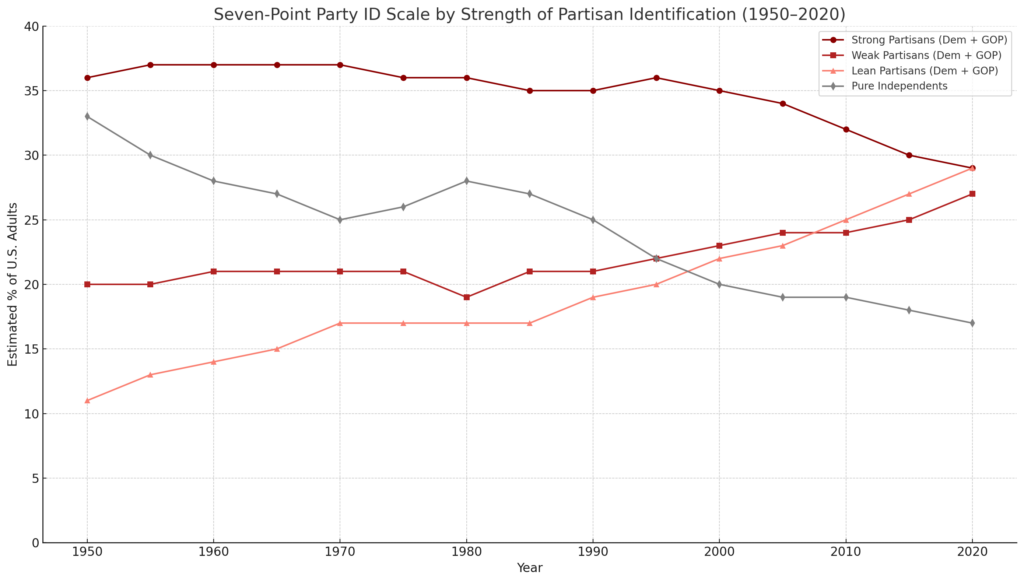

Let’s begin with the basic question: who actually shows up to vote in party primaries? In closed systems—where only registered party members may participate—the electorate is not the full party tent. It is a narrower and more engaged subset. To model this, we can use the widely accepted seven-point party identification scale, which classifies Americans as strong, weak, or lean identifiers.

Before we can reform how we vote in primaries, we must understand who we mean by “the party.” Spoiler: it’s not a monolith.

The chart in Fig. 1 below shows the changing composition of partisan identity in the United States from 1950 to 2020, using this seven-point scale. We’ve disaggregated strong, weak, and lean from independent identifiers. The result is clear: the so-called “base” is not a fixed group. It shifts, fragments, and reassembles over time.

Figure 1. Partisan Identification Trends. the graph showing long-term trends in U.S. partisan identification from 1950 to 2020, grouped by intensity of affiliation: Strong Partisans (dark red): Voters deeply aligned with either the GOP or Democrats. Weak Partisans (firebrick): Voters loosely affiliated with one party. Lean Partisans (salmon): Self-identified independents who lean toward one party. Pure Independents (gray): Voters with no partisan lean and the most potential to swing.

This matters because the voters most likely to show up in a closed primary are the strong partisans—the very voters most likely to be ideologically rigid and least willing to compromise. As leaners and weak identifiers become a larger portion of the electorate, the primary electorate becomes less representative of the party as a whole. That’s not just bad for party unity; it’s bad for democracy.

Approval Voting or RCV can mitigate this effect by rewarding consensus candidates who appeal to both strong partisans and their leaner, less ideologically intense allies. In doing so, they move the party closer to majority rule and away from factional capture.

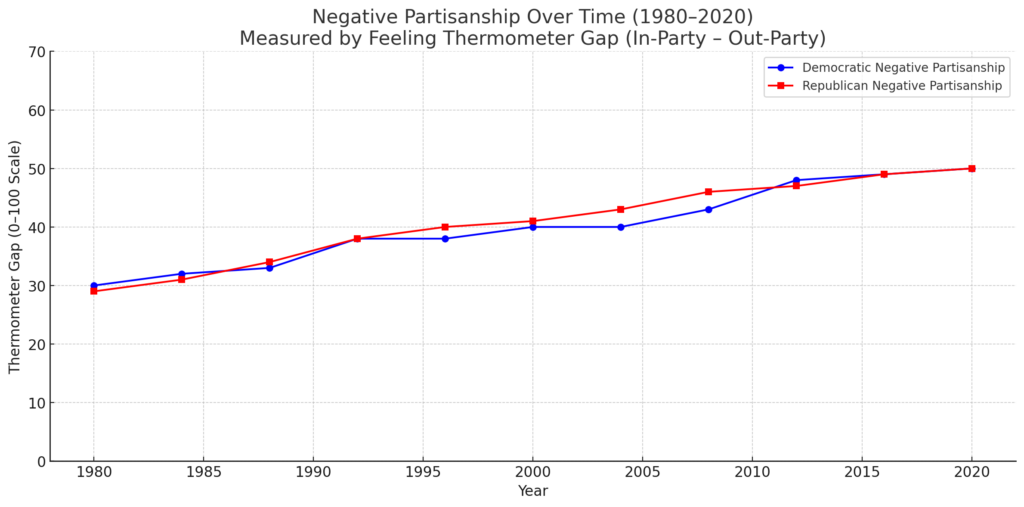

The Thermometer Is Rising: Negative Partisanship Over Time

But what really inflames this distortion is what’s happening inside those primary-voting hearts and minds. Affective polarization—how much partisans dislike the other party—has risen dramatically since 1980. Using data from ANES-style “feeling thermometers” (a 0–100 scale of warmth/coldness toward each party), we can track just how frosty things have become. See Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Negative Partisanship. Here is the chart tracking negative partisanship from 1980 to 2020 using the Feeling Thermometer Gap method, a well-established metric in political science.

Take note: The voters most likely to participate in primaries are the most emotionally polarized. They feel warmly toward their own party and harbor growing hostility toward the opposition. That emotional fuel drives not only more extreme partisan candidate selection but also more punishing general election rhetoric. Such rhetoric may offer short-term gratification for the true believer, but it does little to foster the kind of statesmanship that Madison and Hamilton envisioned—a politics grounded in deliberation, compromise, and the pursuit of national unity over factional triumph.

Implications: Why AV and RCV Matter—Preferring Majorities over Pluralities

In this context, majority-sensitive voting methods like Approval Voting and Ranked Choice Voting offer a lifeline. Even if used within closed primaries, they function as a moderating mechanism:

- AV allows voters to approve of all candidates they find acceptable, diluting the power of ideologues and amplifying consensus.

- RCV ensures that a candidate must win a majority through runoff-style eliminations, discouraging tactical extremism.

These methods don’t fix polarization, but they reshape the incentives. Candidates can no longer win by playing only to the loudest faction. They must appeal to the broader party members.

Bottom Line

If we’re going to maintain closed primaries in an era of high polarization, we must modernize the machinery within them. FPTP was built for a different time. Today’s landscape demands mechanisms that can sift for legitimacy, not just the loudest voices in the room. AV and RCV do just that.

In the age of tribal politics, majority-minded voting reform isn’t just smart—it’s essential.

Conclusion: Toward a More Legitimate Democracy

Closed primaries are not inherently undemocratic. But when combined with plurality voting, they yield nominees who lack majority support, encouraging extremism and disillusionment.

Approval Voting offers a practical solution. It’s simple, majoritarian, and already in use by respected organizations that value fair outcomes. Introducing AV (or RCV) into closed primaries would strengthen democratic legitimacy—restoring trust, reducing polarization, and better aligning candidates with the will of the people.

References

- Arrow, Kenneth. Social Choice and Individual Values. Yale University Press, 1951.

- Condorcet, Marquis de. “Essay on the Application of Mathematics to the Theory of Decision-Making,” 1785.

- Suzuki, Jeff. Constitutional Calculus: The Math of Justice and the Myth of Common Sense. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

- American National Election Studies (ANES), various years.

- Levendusky, Matthew. The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Pew Research Center. “The Partisan Divide on Political Values Grows Even Wider.” October 5, 2017.

- CBS News. “Elon Musk launches attack on Trump, teases new political party.” May 2024.

- FairVote.org. “The Condorcet Winner.” https://www.fairvote.org/condorcet_winner

- Center for Election Science. “Approval Voting in Practice.” https://www.electionscience.org

Disclaimer: Portions of this paper were generated with the help of ChatGPT, who—despite not having voting rights or party affiliation—has strong opinions about Borda counts and Condorcet winners. No robots were harmed in the making of this argument.