It pains me to write this. I have long admired Richard Nixon and Newt Gingrich. Both were brilliant, both were effective, and both reshaped the American political landscape in lasting ways. Yet admiration does not erase consequence. For all they achieved, their choices—alongside reforms that seemed noble at the time—helped assemble the machinery that now drives our polarization.

I know that respect for Nixon and Gingrich is not fashionable. Nixon’s name is still synonymous with scandal. Gingrich is often blamed for breaking Congress. To admit admiration for either is awkward in polite company. Yet their legacies cannot be understood by caricature alone. They were consequential men, and it is precisely because they mattered so much that their choices deserve scrutiny.

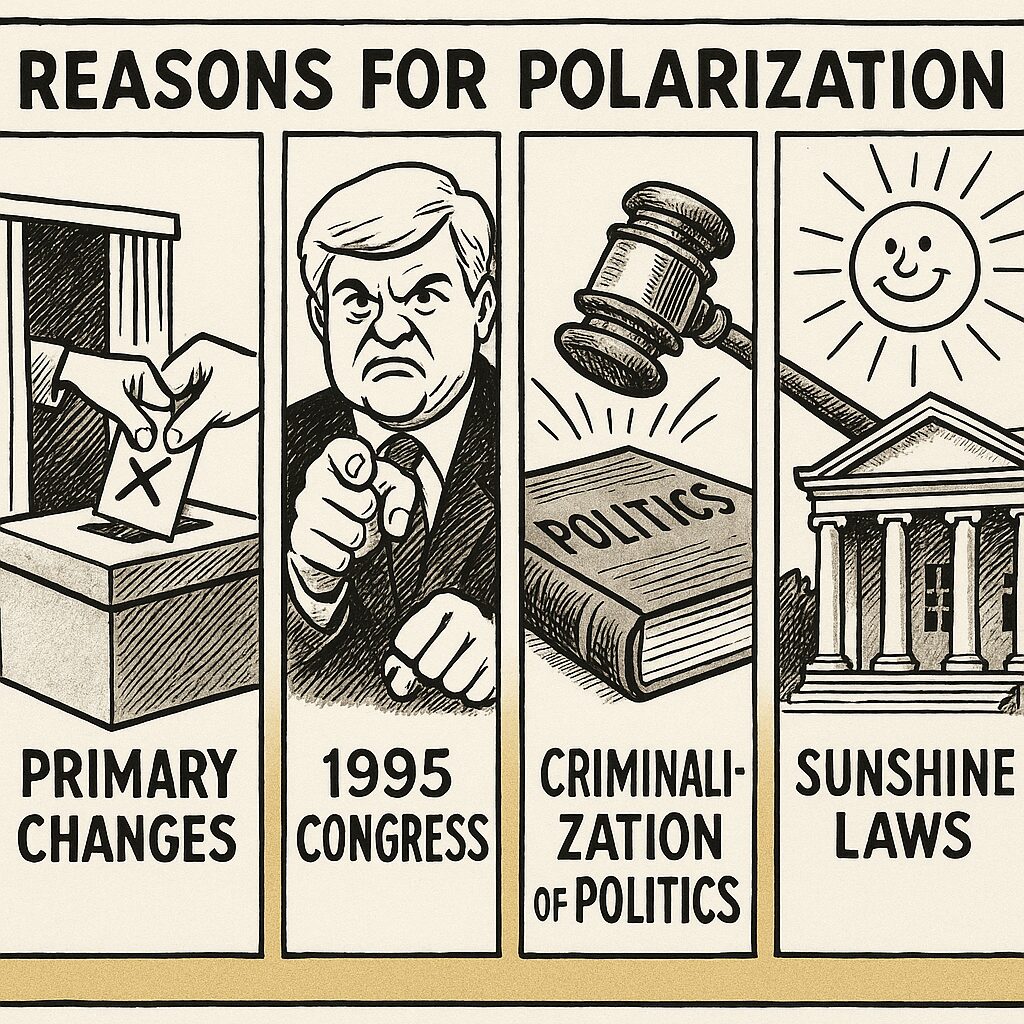

1995: Party Loyalty Over Seniority

I have always respected Gingrich’s drive and vision. His “Contract with America” was nothing less than revolutionary, and he forced Washington to reckon with ideas that had languished for decades. Yet his structural reforms tipped the balance of power in ways that narrowed the room for independent thought.

Committee chairs were no longer chosen by seniority but by party loyalty. Term limits ensured that chairs remained dependent on the Speaker’s favor. The committees lost much of their old independence, and leadership gained control. This was brilliant for enforcing party discipline. It was devastating for fostering bipartisan compromise. Loyalty became the coin of the realm, and moderation became a liability.

Post-Watergate: The Criminalization of Politics

Nixon remains one of the most complex figures in American history. His foreign policy brilliance is unquestioned; his domestic accomplishments were substantial. Yet Watergate was his undoing. His paranoia led to mistakes, and the cover-up sealed his fate.

It is awkward to say aloud that I admire Nixon. To most, he is irredeemable. Yet admiration and honesty require the same thing: facing the whole man, not just the scandal. Nixon’s record at home and abroad was real. So too was the precedent he left behind. Watergate taught both parties that presidents could be taken down by legal means rather than elections. Congress responded with the Ethics in Government Act of 1978, which institutionalized independent counsels. Every president since Reagan has faced some form of special prosecutor or special counsel, with the exception of Obama—though he endured the corrosive birther delegitimization campaign. What was once extraordinary is now expected. Politics became criminalized, and with it came deeper distrust and sharper divisions.

The Machinery Assembled

Each reform was born of good intentions. Each reform had a logic in its own time. Yet together they built the machinery of polarization.

Outsiders dominate presidential elections. Party leaders hold their caucuses in tighter grips. Presidents face legal investigations as a matter of course. Legislators posture in the spotlight, wary of being seen as conciliators.

To admire Nixon or Gingrich is awkward—few would admit it. But history is not obliged to flatter. Both men left their mark on American politics, and both deserve recognition for their talents. At the same time, I cannot deny that the choices they made—combined with broader reforms in primaries and transparency—contributed to the divided politics we endure today.

Polarization is not an accident. It is the sum of reforms and reactions, each carried forward with a logic that seemed necessary at the time. The result is a system that now resists the very compromise it was built to sustain.