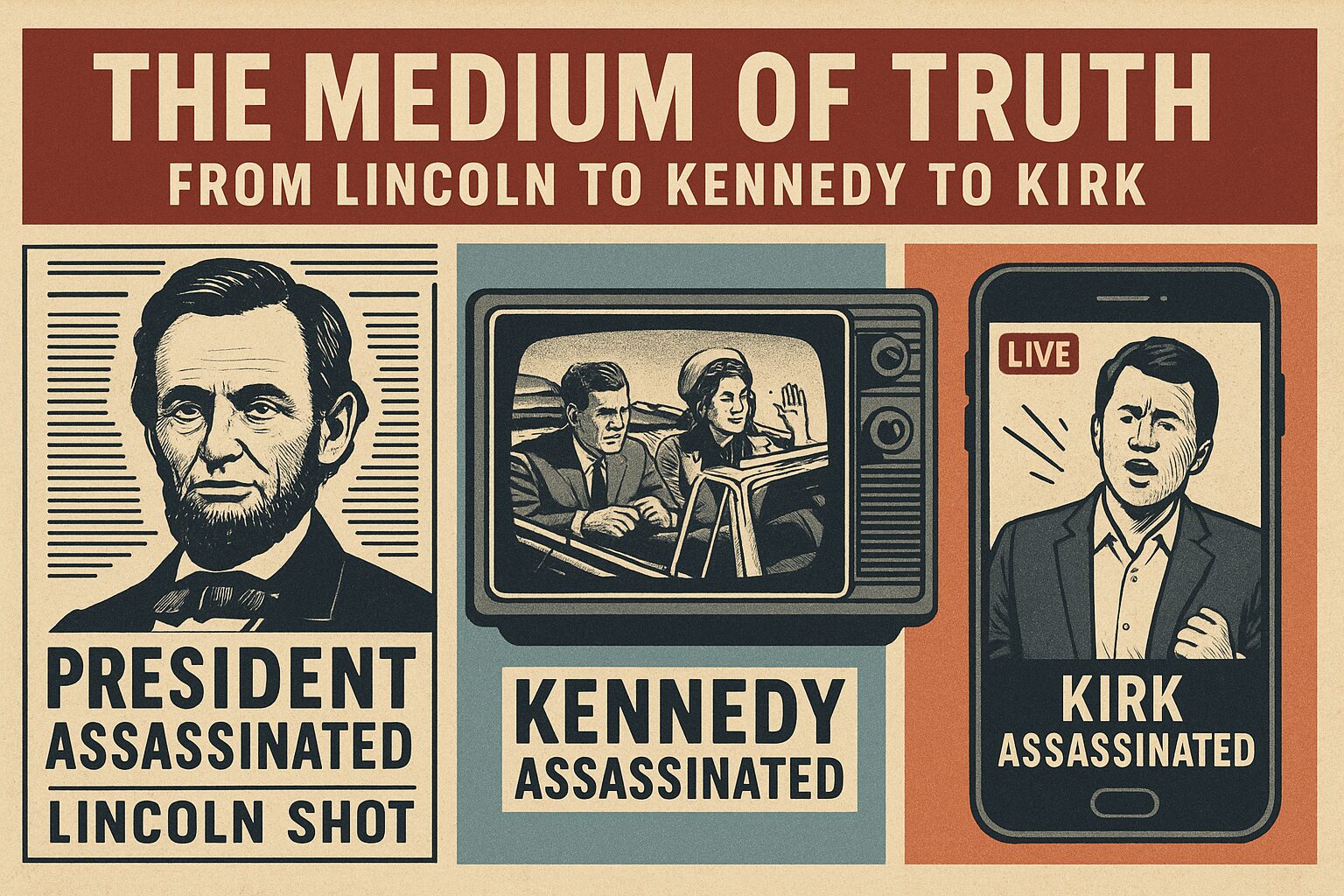

How fast truth travels determines how a nation grieves. In 1865, the newspaper made Lincoln’s death a story of unity and justice. In 1963, television made Kennedy’s death a story of doubt and division. In the digital age, Kirk’s assassination became a story of instant evidence and instant polarization. Each medium has changed not only how we know the truth but how we live with it.

When Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theatre, the Republic moved at the speed of ink. News traveled by telegraph and newspaper, and the official version of events hardened before rumor could multiply. John Wilkes Booth was identified, hunted, and executed within weeks. The medium itself—slow, centralized, and authoritative—made conspiracy nearly impossible. The Union held the pen, and history followed its hand. The nation mourned together, and even those who hated Lincoln conceded the verdict. In a pre-digital world, speed was justice, and monopoly was truth.

A century later, when John F. Kennedy was killed in Dallas, the age of television began to fray that monopoly. The public watched grief in real time: the motorcade, the gunshot, the widow’s veil, the assassin shot on live TV. For the first time, Americans saw the same tragedy through the same lens—and yet drew different conclusions. The Warren Commission published its report, but millions had already watched the Zapruder film and reached their own verdict. Seeing was no longer believing. The medium had changed: the faster the feed, the deeper the doubt. Conspiracy multiplied not in the shadows but in the light.

Now, in the digital era, the story completes its circuit. When Charlie Kirk was assassinated, every angle appeared online before the police tape settled. Eyewitness videos, satellite imagery, and timestamped posts created a living archive that no theory could outrun. For the first time, the crowd itself became the Warren Commission. The raw data extinguished the conspiracy before it could catch flame. Yet the same torrent that killed the myth also hardened the divide. Each side saw proof of what it already believed. Truth was not deliberated; it was downloaded.

The medium of information has always shaped the republic’s moral tempo. The telegraph enforced unity by limiting choice. Television democratized perception and sowed doubt. The internet has democratized judgment itself—every citizen now prosecutor, witness, and juror. Each leap forward has made truth faster, but also more fragmented.

Madison’s Ghost in the Machine

James Madison warned that the greatest threat to liberty was faction—citizens united by passion rather than reason. His cure was scale and delay: an extended republic with representatives who would cool the public temper. What he could not foresee was a world where technology would dissolve the very friction he designed. Social media collapses time, distance, and deliberation. It allows passions to surge across a continent in seconds, forming coalitions that share emotion but not substance.

The January 6 riot is the purest example. Social media yoked a heterogeneous crowd together—people from distant states, sharing little beyond a common feed. Their unity was algorithmic, not ideological. They were bound by reaction, not reflection. As Ben Hamilton’s eyewitness account shows, digital shame replaced deliberative law. Within hours, families and friends were identifying rioters online, publicly condemning them before the courts could convene. Justice moved at the speed of the screenshot.

Madison’s system depended on time to convert emotion into policy. Digital media compresses that interval to zero. We have achieved unity without understanding, and immediacy without coherence. The result is a republic of permanent reaction.

From Faction to Flash Mob

Lincoln’s America could only move as fast as the typesetter. Kennedy’s could move as fast as the camera. Ours moves as fast as the click. The consequence is not simply more information, but more simultaneous emotion. We feel together before we think together. The crowd that once gathered in courtyards now gathers in comment threads. The riot has gone wireless.

And yet, the digital crowd is curiously hollow. Like the youth of 1968 who disrupted the Democratic Convention—Abbie Hoffman’s “we couldn’t agree on lunch” generation—the January 6 mob shared outrage but not objective. It was, in Madison’s terms, a faction without a philosophy. Passion united them; purpose dissolved them.

The New Republic of Speed

From Ford’s Theatre to Dealey Plaza to the digital feed, each medium has rewritten the balance between passion and reason. Newspapers constrained faction through slowness. Television expanded it through spectacle. Social media has made it omnipresent and incoherent—a chorus of millions shouting in real time with no conductor.

The republic still stands, but Madison’s cooling mechanisms—distance, delay, representation—are melting in the heat of the network. The question now is not how to stop the noise, but how to slow it—how to restore the pause that once made republican self-government possible.

Because the medium that once bound us together now binds us to the instant.

Slow down—before the scroll becomes the mob

The Founders built a republic of pauses—a system of speed bumps against the rush of passion. Our technology has stripped them away. The question now is whether citizens can rebuild those pauses within themselves. In an age where every fact arrives before we can think, self-government begins with restraint. Can we still choose to wait before we join the mob?

Written with a little help from ChatGPT—which, unlike Congress, met every deadline.