A new talking point circulates through certain corners of the Internet: America is a nation of settlers, not immigrants.

The phrase sounds proud, clean, and self-reliant—a rhetorical border wall separating the virtuous founders from the needy newcomers.

But history tells a humbler story.

Part I — Financed Settlers with Resupply

The first Europeans in North America were not the authors of independence. They were the clients of empire—state-sponsored dependents whose survival rested on outside help.

The Lost Colony: When the Subsidy Stopped

The colony of Roanoke proves the rule.

Planted in 1587 under an English charter, the settlement vanished within three years when resupply ships failed to arrive. The governor returned to find the word Croatoan carved into a post and no souls left to explain it. Roanoke was what happens when the money, ships, and soldiers stop coming. The dream of self-made settlement died with them.

Every colony that endured did so under constant European support—charters, investors, and fleets of resupply. Jamestown, founded two decades later, was a venture of the Virginia Company and survived only because England kept sending men, weapons, and provisions. Even then, two-thirds of the colonists perished in the first year.

The Pilgrims at Plymouth were no freer. Their voyage was financed by London investors who owned half of whatever they produced. Their first winter killed half of them, and the survivors lived because the Wampanoag taught them how to plant corn, fish, and survive a climate they did not understand.

Remove the imperial lifeline, and the “self-made” settler disappears.

Saved by Mercy, Not Might

The early English colonies did not conquer a continent—they clung to its edges by permission. Indigenous nations held overwhelming power in those first decades. The Powhatan Confederacy surrounding Jamestown could have erased the colony at any moment. In 1622, they nearly did—killing a quarter of the settlers in a single day. Only new reinforcements from England and brutal reprisals kept the outpost alive.

In New England, the Wampanoag spared Plymouth not because they could not destroy it, but because they sought allies against rival tribes. When that alliance broke a generation later, King Philip’s War nearly ended English settlement altogether. Entire towns were burned; one in ten colonists died. The English survived because other Native nations joined them—and because fresh gunpowder kept arriving from across the Atlantic.

Elsewhere, the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 expelled the Spanish from New Mexico for over a decade. The French survived only through Indigenous alliances. The record is clear: the “settlers” were not masters of the New World; they were guests whose welcome could be withdrawn.

Dependence in Disguise

The romantic image of the self-reliant settler was a story invented later, by descendants who preferred pride to accuracy. The truth is that colonists relied on a triangle of dependence: European finance, Indigenous tolerance, and enslaved labor. Remove any side, and the colonial enterprise collapses.

Today’s immigrants come with none of the settlers’ privileges—no crown charter, no land grants, no standing army, and no captive labor. They cross oceans at personal risk, not at the expense of royal subsidies. The first Europeans proved one truth beyond argument: no one builds alone. They survived by grace as much as grit. They were saved by those they did not understand and often betrayed. That dependence is not shameful—it is human. The shame lies in forgetting it.

America did not begin as a purely self-made nation. It began as a dependent colony that learned, painfully, how to grow free. Every immigrant since has walked the same road, without the empire behind them.

We were not settlers instead of immigrants.

We were immigrants first, and we still are.

Part II — The Curve of a Nation

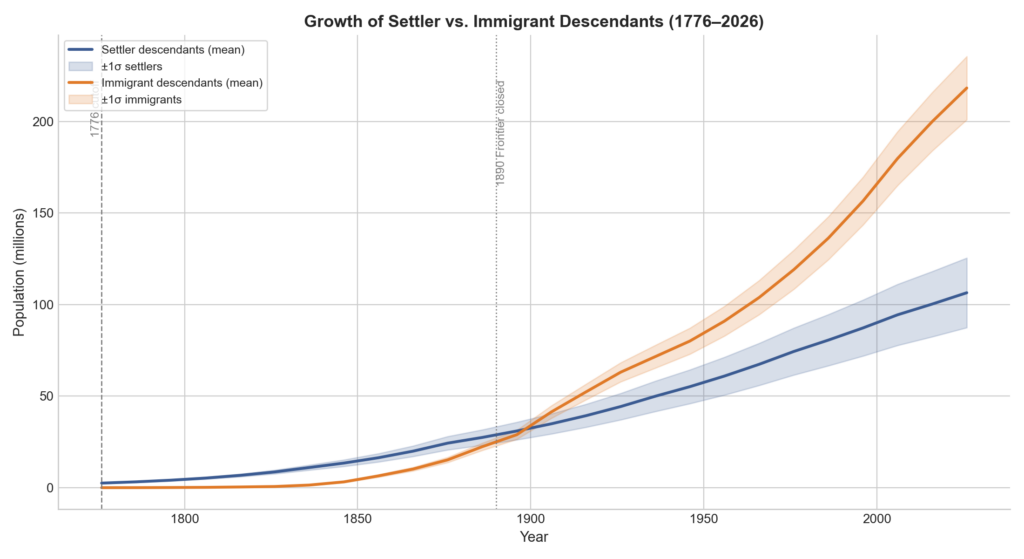

History tells one story; numbers tell the same.

If we draw an arbitrary but reasonable line at 1776—calling everyone before that year a settler and everyone after an immigrant—we can model how each group’s descendants contributed to the nation’s population.

To do so, I seeded 1776 with an estimated 2.5 million people, including the enslaved, and treated them as “settlers.” Their growth after independence reflects only natural increase—births minus deaths—within the closed population.

From 1776 forward, I added documented immigration inflows by decade and let those new arrivals grow at the same natural rate. The model spans 1776 to 2026, calibrated against every U.S. Census from 1790 through 2020.

The chart below shows the results of 2,000 Monte Carlo simulations, each introducing small random variations in fertility, mortality, and immigration to reflect uncertainty.

Mean ± 1 σ confidence bands. Blue = descendants of pre-1776 settlers. Orange = descendants of post-1776 immigrants.

For the first century, the United States remained largely a nation of settler descendants.

By 1900, the curves crossed.

The orange line—immigrant descendants—surpassed the blue line and has led ever since.

The transition coincides with the closing of the frontier and the mass arrivals of the industrial era. By 2026, the model estimates roughly 106 million settler-descended Americans and over 200 million immigrant-descended Americans.

The shaded bands mark uncertainty, but the trend is unmistakable. The myth of the “settler nation” dissolves in arithmetic. The colony that began as a dependency of empire has become a republic built by waves of newcomers.

Assumptions and Transparency

- Cutoff Year = 1776.

Before independence, inhabitants were colonial subjects—settlers. After independence, entrants joined a nation—immigrants. - Initial Population = 2.5 million.

Based on historical estimates for the 13 colonies, including enslaved people, who were integral to survival and therefore to the settler population. - Natural Growth Rates.

Varying by era, higher in the early republic and gradually declining to modern levels, drawn randomly within documented historical ranges. - Immigration Data.

Decadal inflows taken from historical compendia (1820 onward) and reasonable estimates for earlier decades, with ±20 percent noise for uncertainty. - Validation.

Model totals were compared to U.S. Census counts each decade; the mean trajectory remains within a few million of observed history.

These assumptions can be debated—but the direction of the curve cannot. However one draws the boundaries, the nation’s growth has depended far more on immigration than on settler population growth.

Rebutting the Settler Myth

The “settlers vs. immigrants” distinction collapses under both history and mathematics. The settlers were financed, supplied, and protected by Europe. If settlers built the beachhead, immigrants built the continent.

Download and Replicate

The analysis is open for inspection and improvement. Anyone may reproduce the results or adjust the assumptions:

Run it, challenge it, refine it. That is the strength of both science and democracy—the willingness to test what we believe.

The transition from a nation of settlers to a nation of immigrants was not a moral decline but a mathematical inevitability—the moment when the Republic began reproducing itself not through empire, but through welcome. The curve makes plain what the Founders only hoped: that America’s growth, like its freedom, would depend on the courage of those who came next.

David L. Page, Ph.D. — davidpage@ieee.org

Disclaimer:

This essay was developed with research, drafting, and visualization assistance from ChatGPT (GPT-5). All interpretations, historical framing, and conclusions are my own. Artificial intelligence helped organize data and render figures—but not the argument.