Why a Two-Party System Remains the Hardest, and Best, Path to Democratic Compromise

Government is the only institution in society that holds a lawful monopoly over violence. That simple fact often hides in plain sight, yet it shapes every political design from the ancient world to the present. When a society grants that monopoly to a central authority, the question immediately follows: Who guards the guardians? Who directs the power that directs everyone else?

Democracy emerged as the best answer human beings have ever discovered. A majority can guide the state, and that majority can change with the next election. No bloodlines. No dynasties. No divine right to rule. The people choose, and the people can choose differently. Yet the very principle that gives democracy its strength also carries its most dangerous weakness. A majority can govern. A majority can also abuse.

Direct democracies often fall to demagogues who exploit passion, grievance, and spectacle. History supplies many examples. A leader skilled in manipulating the crowd can turn majority rule into majority rage. Demagoguery rises quickly, and it collapses just as quickly, usually after inflicting real harm on those unable to resist a whipped-up public.

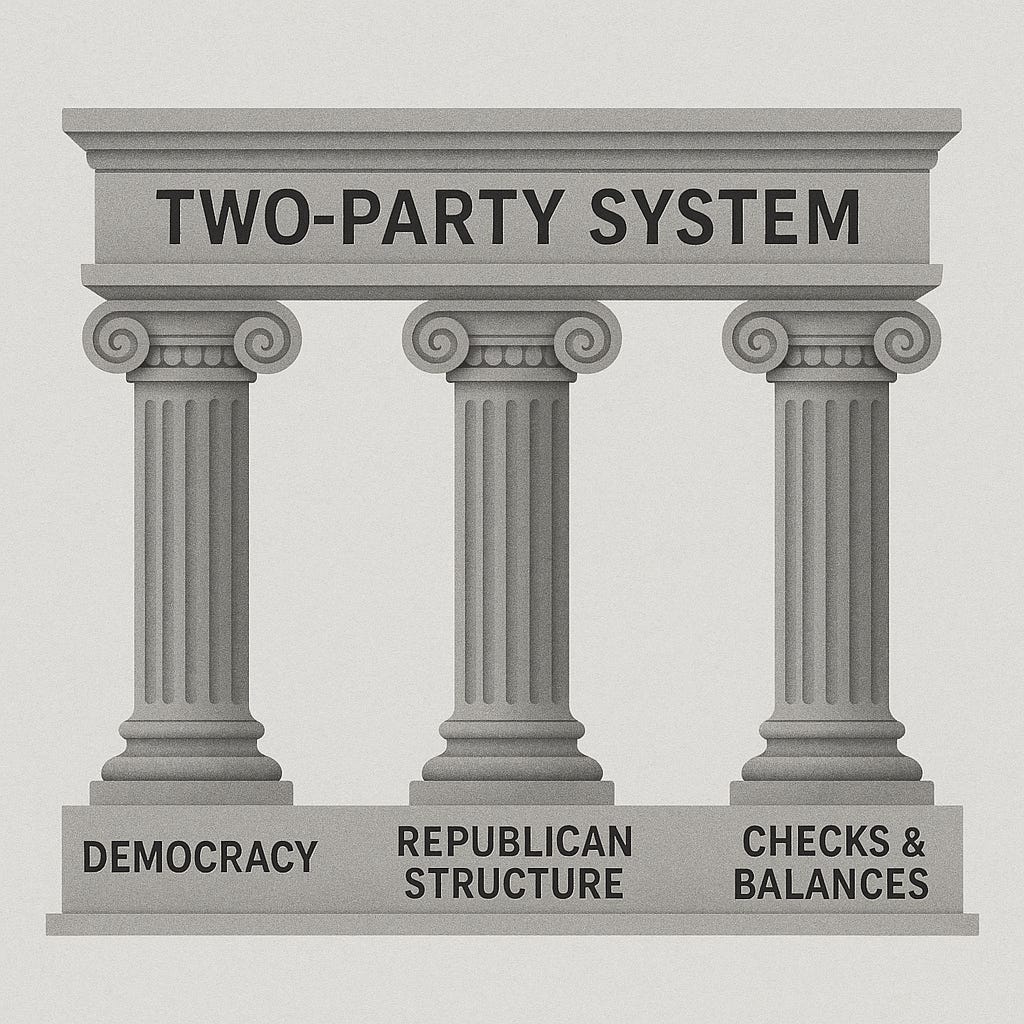

The American founders understood this danger. They placed republican structure between the people and the raw exercise of state power. Representatives must deliberate. Institutions must check one another. The process must slow the impulse of a moment so that a temporary majority cannot impose permanent damage on a minority. The architecture was not designed to silence the people. The architecture was designed to give the people time to think.

From that design emerged a practical political truth: republican systems work best when they push political integration before the election rather than after it. A two-party system forces factions to bargain, trade, and cohere inside the coalition long before voters cast ballots. Each party must become a broad tent. Each party must build a platform that can attract enough citizens across the social and geographic divides of a large republic. Compromise occurs upstream.

Multi-party systems invert that sequence. Parties appeal to narrow constituencies, gain seats in parliament, and then discover that a governing majority requires a post-election coalition. Compromise arrives after voters have already spoken. That second-order bargaining often creates instability and opacity. Citizens vote for a party, then watch that party bend itself into shapes never described on the campaign trail.

The endurance of the American Republic underscores the value of this design. The United States remains the oldest continuous constitutional democracy in the world, in part because its structure compels political integration before power is exercised. By contrast, the European Union, built from a patchwork of parliamentary systems and national parties, often struggles to speak or act with one voice. Its many coalitions form only after elections, which leaves the Union perpetually negotiating itself before it can negotiate for its people.

A two-party republic does not require harmony. It requires integration. It requires citizens willing to join coalitions broader than their preferences. It requires leaders willing to accept that governing a free people means navigating the space between disagreement and destruction.

Compromise is never easy, and it is not for the weak. Yet the republic depends on those who choose to do the work before the election rather than after the damage has already been done.

Disclaimer: This essay was prepared with editorial assistance from ChatGPT, who offered helpful suggestions without demanding a seat in Congress or attempting to form a third party.