I first learned about Antonio Gramsci over donuts with two friends at one of our “Donuts for Democracy” discussions. We were wrestling with how ideas that begin on the fringe can reshape institutions and norms over time, as we discussed the first chapter of The Art of the Compromise. Gramsci’s name came up as someone whose work helped explain not just how power operates, but how it evolves—and as my friend described in the context of DEI, Diversity Equity, and Inclusion, movement in the headlines today. That conversation sent me down a path that led to an unexpected tension in my own views—between supporting the ideals behind diversity and inclusion, and growing uneasy with how those ideals are increasingly implemented through institutional force.

To understand that tension, we need to start with Gramsci himself.

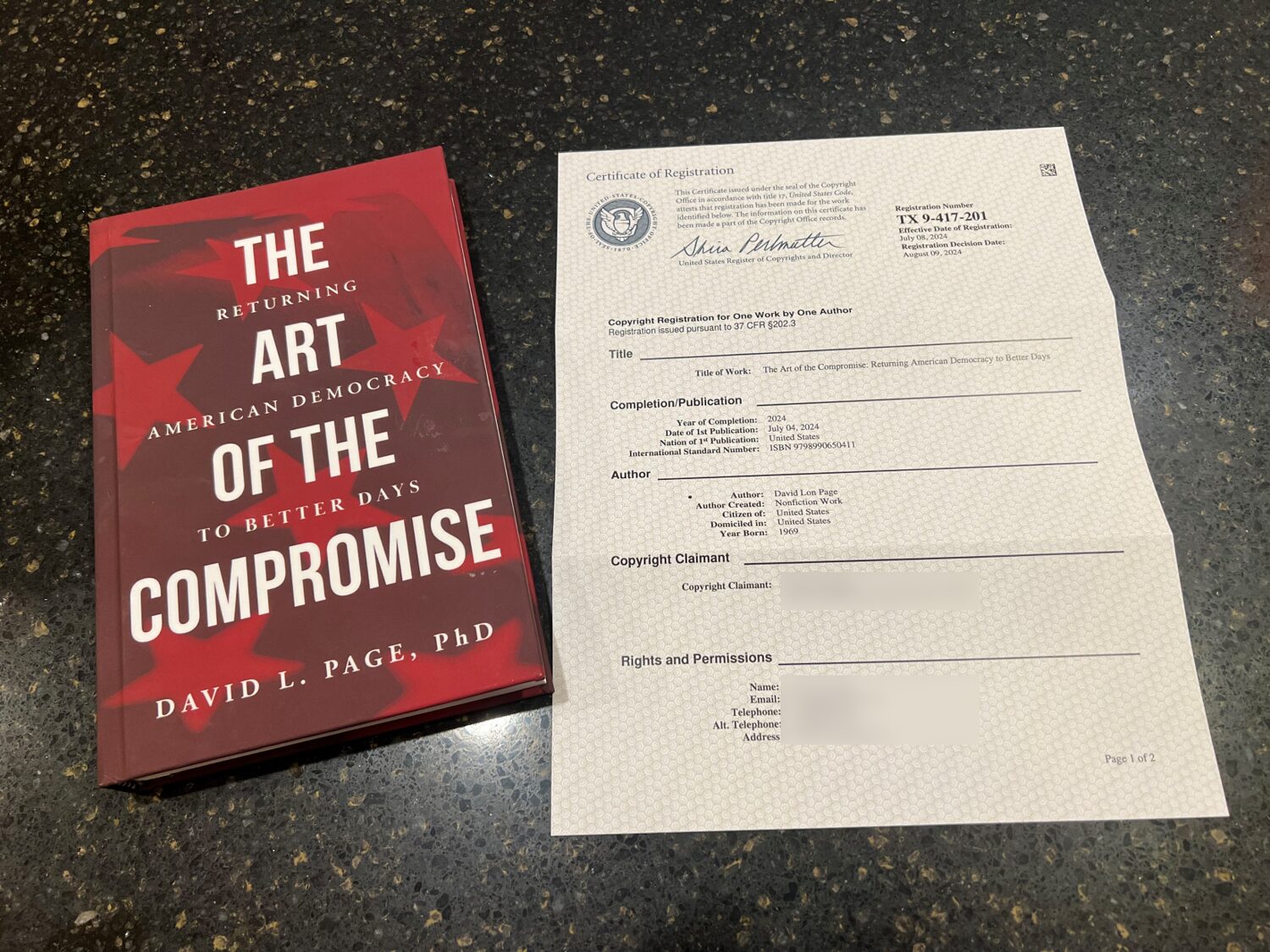

Gramsci in Historical Context

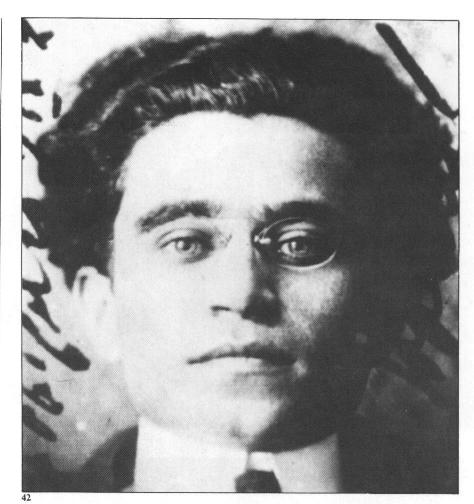

Antonio Gramsci was imprisoned by Mussolini’s fascist regime in the 1920s. While behind bars, he wrote his Prison Notebooks, a collection of reflections on politics, society, and culture that would change Marxist theory.

Gramsci was grappling with a major question. Why had Marxist revolution succeeded in places like Russia but failed in the more advanced capitalist democracies of Western Europe? His answer was subtle but profound. In the West, power was maintained through cultural hegemony—the dominance of ideas, values, and norms that made the capitalist order feel natural, even moral. The ruling class didn’t just control the economy; they also shaped what people believed was possible and right. Gramsci realized that the culture of Western Europe was not ready for Marxism.

Antonio Gramsci, 1915. Public Domain photo.

From Revolution to “Cultural Struggle”

Classical Marxism assumed that revolution would arise from worsening economic conditions and that Western Europe would naturally transition into Marxist revolution. Yet, when it didn’t, Gramsci saw that in the West, civil society—schools, churches, newspapers, and cultural institutions—served as buffers, absorbing unrest and neutralizing it. To challenge the system, Marxists would need a new strategy—a “war of position.” Gramsci said this war was a long-term, ideological, and cultural struggle to create counter-hegemony.

This strategy, born from Gramsci’s frustrations with failed Marxist revolution, would influence the New Left in the 1960s and 70s and, indirectly, many of the theoretical foundations of DEI today.

DEI as Counter-Hegemony

Modern DEI efforts often begin—sometimes unknowingly—from a Gramscian premise that systems of oppression are not maintained solely by law or brute force but through everyday norms, unexamined language, and institutional habits. To make society more just, these structures must be identified, named, and dismantled, starting in the workplace, the pulpit, the classroom, and the media.

When DEI asks us to interrogate language, modify sermons, rethink historical narratives, or implement new training and policy frameworks, it is not simply doing HR reform. It is engaged in what Gramsci would have called a project of counter-hegemony—an effort to reshape the dominant cultural framework, often through slow institutional transformation.

DEI is more than just a moral appeal to fairness. The movement has come to operate with the intensity and certainty of a “secular” faith. Here’s where my personal discomfort begins to take root.

The Dilemma: Supporting Inclusion, Resisting Imposition

I believe deeply in the moral importance of inclusion and fairness. I want diverse perspectives at the table. I believe America’s strength lies in our diversity of ideas. I want institutions to reflect the complexity of the society they serve. But I also believe in the liberal values of open inquiry, freedom of conscience, and the idea that moral belief cannot and should not be coerced by the state or by institutions acting in its stead.

Too often, DEI in its modern form feels less like an invitation and more like an imposition. It borrows the logic of hegemony itself, replacing one orthodoxy with another. In place of pluralism, we get dogma. In place of dialogue, we get declarations. What began as a call for equity risks becoming a new regime of moral surveillance.

And so, I find myself split. I am of two minds. I am sympathetic to the ideals behind DEI, but uneasy with its implementation, especially when backed by the power of the state, the HR department, or the university administration.

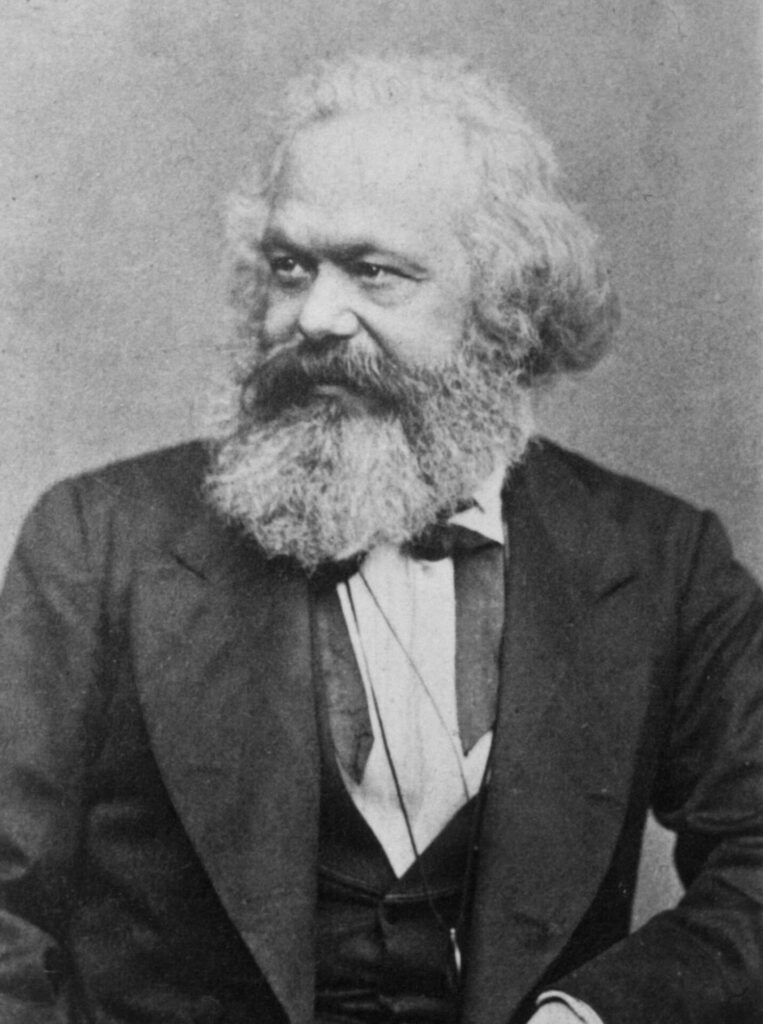

Karl Marx, 1871, Image by John Jabez Edwin Mayall, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Gramsci’s American Translator—and a Political Legacy

As an intriguing aside, Gramsci’s story gets more interesting when we look at how Gramsci came to American audiences. His Prison Notebooks, originally written in Italian, were translated into English thanks to Joseph Buttigieg, a professor of literature and a co-founder of the International Gramsci Society. Joseph wasn’t just a translator, but he was also a devoted interpreter of Gramsci’s belief that culture was the real battlefield of politics.

Joseph’s son, Pete Buttigieg, rose to national prominence as a presidential candidate and served as the U.S. Secretary of Transportation under Biden. During his campaign, Pete was often asked about his father’s Marxist scholarship. He didn’t disavow it, but he did steer away from it, either. He crafted himself as a pragmatic, technocratic centrist rather than an ideological heir to his father’s radical roots.

Pete’s quiet distancing speaks volumes. It shows how radical ideas, like Gramsci’s, can enter the mainstream, not by storming it, but by being absorbed and domesticated by institutions. Pete Buttigieg represents a version of Gramscian thought without the revolutionary posture—institutionally embedded, highly educated, rhetorically inclusive, and strategically moderate.

In many ways, that is what DEI has become: the institutionalization of what began as a counter-hegemonic project. The radical origins are still there, yet they’ve been translated—both literally and metaphorically—into a new form of authority.

Pete Buttigieg, one-time Democratic presidential candidate, whose father Joe Buttigieg translated Gramsci’s works for modern American consumption. Image by Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Conclusion: Gramsci’s Ghost in the Machine

Gramsci helps us understand not just the philosophical underpinnings of DEI, but why it feels both revolutionary and institutional at once. His vision of cultural struggle is alive in these efforts, but so is his recognition that ideas, once dominant, become invisible and uncontestable.

That’s the paradox. DEI, as a counter-hegemonic movement, may already be becoming hegemonic itself. And if we’re not careful, in our rush to do good, we risk creating a system that punishes dissent rather than fosters genuine inclusion.

Not all things that sound good are good. And sometimes, as Gramsci himself might remind us, power hides best when it speaks in the language of virtue.

Disputes: All disputes to the arguments in the blog post will be handled by Rock, Paper, Scissors.

Disclaimer: I wrote the original draft of this blog post and then prompted ChatGPT to polish that draft and provide an image for illustration.