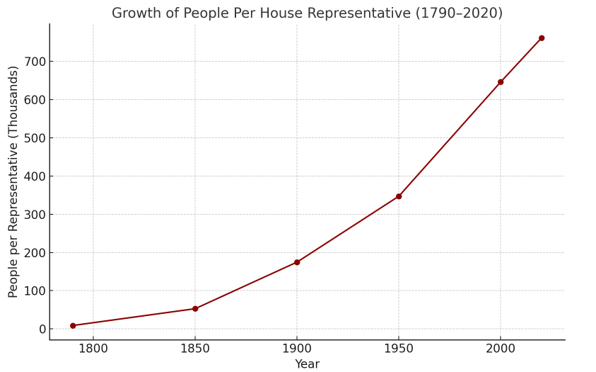

Late in the summer of 1787, as the Constitutional Convention strained toward consensus, one thing united even its most fractious factions: the House of Representatives would be the chamber “closest to the people.” So close, in fact, that in the very first Congress, each Representative served about 30,000 citizens. It was a scale that presumed proximity—of values, of neighborhoods, and yes, even of memory. You might not know your congressman personally, but someone in your church or town probably did.

Fast forward to today. That number has ballooned. As of the 2020 census, each Representative now speaks for an average of 761,169 people. At that scale, you’re more likely to win the lottery than have a meaningful conversation with your elected voice in Congress. The chamber closest to the people now operates at a distance so great that proximity is no longer physical or even philosophical—it’s algorithmic.

So what changed?

Not the Constitution. Not the census. Just the will to adjust. The size of the House has been frozen at 435 since 1929, even as the population has tripled. We didn’t adapt the structure to the growth. We just scaled up the expectations of the people inside it.

That brings us to the real problem: humans don’t scale well.

This chart shows how representation has ballooned from about 60,000 people per representative in 1790 to over 760,000 today—an eleven-fold increase. This shift runs counter to the Constitution’s original intent to maintain close constituent contact.

The Limits of Representation—and the Brain

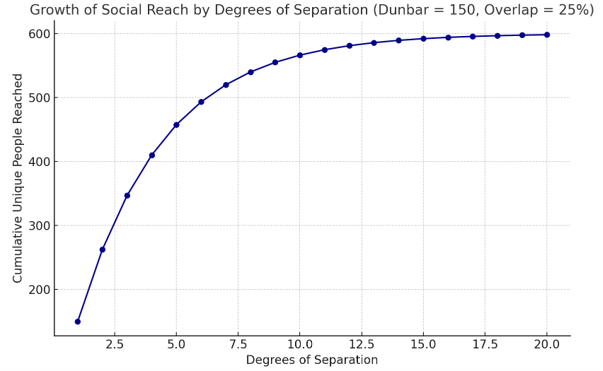

Anthropologist Robin Dunbar proposed that humans can only maintain stable social relationships with around 150 people—a number not based on politics or ideology but on neocortical processing capacity. It’s what we’re wired for. This so-called Dunbar’s Number shows up everywhere: from Neolithic villages to military units, Amish communities to effective startup teams.

Now apply that to Congress. One House member trying to represent 700,000 people? That’s over 4,600 Dunbar-sized clusters, each with its own concerns, values, and vocabulary. And that’s assuming people are evenly distributed—which, of course, they are not. In the real world, representation is not just a matter of math. It’s a matter of networks.

In network theory, there’s a well-known concept: clustering. Our social worlds are not random; they’re clumped. Your friends know each other. Your town council and PTA might share a few of the same names. This clustering creates redundancy, but it also creates friction. It means that information travels quickly within a group, but slowly across them. It means that the bigger the group, the more you lose sight of the edges.

And this is the fatal flaw of the modern congressional district. At 700,000 people, a single representative is simply too far removed to hear the signal through the noise. The problem isn’t that Congress is out of touch. It’s that it’s trying to stay in touch with too many people, using mechanisms never designed to bridge that cognitive and social gap.

This plot models how social networks grow with each degree of separation, assuming each person can know 150 others and that 25% of those ties overlap with others’. You’ll notice the network saturates quickly (~600 people)—far less than 700,000. A single representative cannot meaningfully absorb the needs of their entire district without intermediaries.

A Modern Fix Rooted in Old Logic

I’m not proposing we expand the House to 6,000 members (though if we had kept to the 1790 ratio, that’s where we’d be). I’m also not proposing that Representatives personally know everyone in their districts. That’s impossible—and unnecessary.

But I am proposing that we restructure how representation works inside a district. Not by rewriting the Constitution, but by recognizing that the brain still matters—and so does structure.

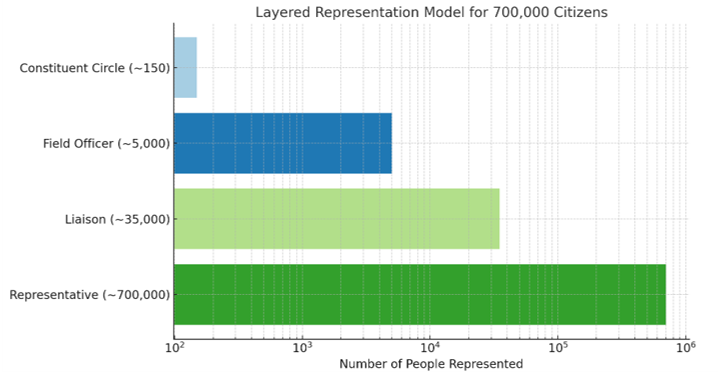

What we need is a layered delegation model—a fractal pattern of representation that acknowledges the cognitive limits of individuals and the complexity of the communities they serve. It’s not a new idea. The Catholic Church has used it for centuries. So have the military, tribal councils, and successful political machines from Tammany Hall to Obama’s field operations.

A Four-Tier Model for Cognitive Democracy

Here’s how it works. At the bottom, we embrace the Dunbar unit: clusters of roughly 150 people—neighborhood groups, congregations, civic clubs, school boards. These are the relational cores of a community, and they form the base.

Above them, we place field officers—community observers and communicators responsible for about 5,000 people each. These aren’t campaign volunteers; they’re embedded civic translators who attend local meetings, identify emergent issues, and report upward.

Next come constituent liaisons, each responsible for around 30,000–35,000 constituents. This is the population size that the Founders actually worked with—and what early 19th-century representatives could realistically understand. These liaisons serve as regional managers of trust: they oversee engagement, coordinate field reports, and synthesize what’s happening across communities.

At the top is the House Representative, now not flying blind but embedded in a living network of relational intelligence. The Representative still casts the vote, gives the speech, negotiates the bill. But the inputs to those actions no longer come solely from lobbyists, donors, or Twitter. They come from citizens, channeled through a structure that mirrors the scale of real life.

The Numbers, Visualized

This diagram introduces a fractal delegation model.

We’re talking about a system where each Representative governs a structure like this:

- ~4,600 Dunbar clusters → each rooted in neighborhoods, churches, or local institutions

- ~130 field officers → gathering data, building bridges, amplifying voices

- ~20 liaisons → integrating the signals into coherent district-level feedback

- 1 Representative → accountable not just to 700,000, but to a structure built for scale

Why It Works

This model doesn’t require a constitutional amendment or a massive budget increase. It requires a shift in how we think about representation: not as heroic individualism, but as structured empathy.

It acknowledges what network scientists, anthropologists, and frustrated constituents already know: the current model doesn’t work—not because our Representatives don’t care, but because we’ve asked them to do the cognitively impossible.

The good news is, we can fix that. We can rebuild Congress’s connection to the people not by shrinking the people, but by building a better bridge—one layer at a time.

Disclosure:

Parts of this post were developed with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model created by OpenAI. While the arguments and perspectives are my own, I used AI as a collaborative research and drafting tool to organize thoughts, generate visualizations, and refine language. Any errors in judgment, interpretation, or history are still mine to claim.