How a shared language lets democracy scale

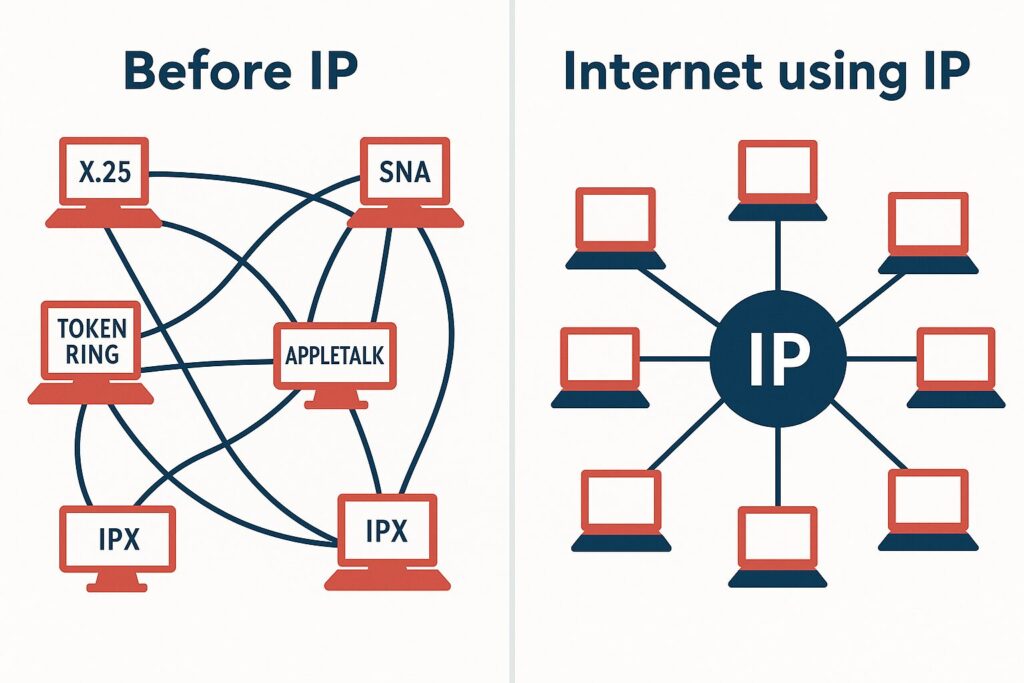

Before the Internet became the Internet, it was a patchwork of isolated networks. IBM had its system. So did DEC. So did the Department of Defense. Each one had its own language, its own way of passing messages—incompatible, tangled, provincial.

And then came TCP/IP. It didn’t erase diversity. It didn’t dictate content. It simply offered a common protocol—a shared set of expectations about how information should flow. Suddenly, the world connected. The network effect ignited. Systems that once sat like islands began to speak, and everything changed.

Now imagine democracy as a kind of social network.

Democracy as a Human Protocol Stack

A large, pluralistic republic like the United States doesn’t run on ethnicity, religion, or regional loyalty. It runs on communication. Not just speech, but shared understanding. The ability to reason together across distance, difference, and disagreement.

That doesn’t require uniformity. But it does require interoperability.

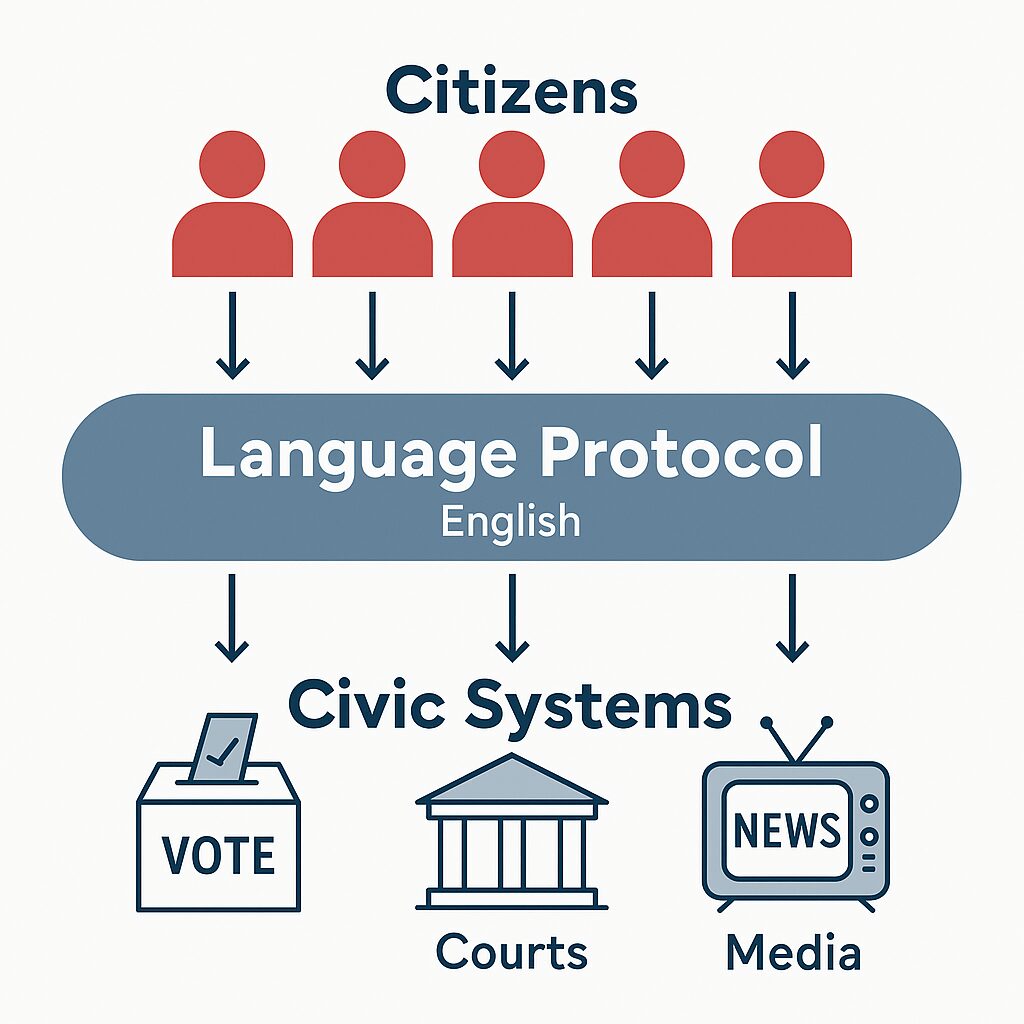

Just as TCP/IP connected computers, a common civic language connects citizens. It allows a voter in Mississippi to argue with a legislator from Oregon, a journalist in Chicago to question a general from Texas. English, in this sense, is our TCP/IP—not because it’s perfect, but because it is shared. It carries the payload of democracy.

But there’s a deeper layer too.

XML for the Republic

If TCP/IP is about connection, then XML (Extensible Markup Language) is about structure. It’s what lets two systems not just share data, but agree on what that data means.

XML is humble. It doesn’t tell you what to say. It just asks you to tag your inputs. It enables context. It defines the conversation.

So does language.

A shared civic language isn’t just about talking. It’s about tagging meaning.

When someone says “justice,” do they mean law enforcement? Or equity? When they say “freedom,” do they mean protection from government? Or protection through it?

Without a shared schema, those words bounce around like malformed packets.

Civic XML: Why Language Matters More Than Ever

We live in an age of semantic overload. Social media flattens context. Cable news fragments vocabulary. We use the same words—but our meanings diverge.

That’s where English, as a civic language, does its quiet work. Not as a marker of purity, but as a protocol of participation. It’s what lets school board meetings, courtrooms, and campaign debates function like routers in a political network.

This doesn’t mean other languages should be erased. It means English remains the parsing layer for collective governance.

When done well, that layer invites more people in. It empowers immigrants. It bridges class divides. It lets a nation scale.

The Ask: Build the Protocol, Don’t Mandate It

Like TCP/IP or XML, a shared language works best when it’s adopted, not imposed.

So instead of declaring English the official language by statute, we should:

- Teach it as a tool of democratic participation, not just grammar drills.

- Fund multilingual materials that converge back to shared meanings.

- Incentivize clarity, simplicity, and accessibility in civic writing.

Let English remain what it has always been in America: the voluntary handshake, the handshake that lets strangers govern together.

Author’s Note:

This post was written with help from ChatGPT, who served as my research assistant, draft whisperer, and occasional devil’s advocate. While I supplied the brainwaves, it handled the caffeine-free typing. Any errors are mine. Any unusually clever metaphors probably aren’t.