What Korea and Turkey can teach America about language, identity, and soft power

The United States has pulled off something most nations only dream of: unifying a massive, diverse population without ever imposing a national language. There is no “English Act.” No Ministry of Language. Just a strong gravitational pull.

But history gives us some powerful counterexamples—cases where nations did mandate a shared language. And it worked. Mostly.

Let’s take a brief tour through two remarkable efforts: Korea’s Hangul and Turkey’s alphabet revolution under Atatürk. These are not cautionary tales. They’re case studies in how language policy can work—when aligned with national identity and historical rupture. And they help explain why America took a different road.

Korea: A Script for the People

In 1443, King Sejong invented Hangul, a phonetic alphabet designed to replace Chinese characters (Hanja) and make literacy accessible to all Koreans.

But the elites resisted. For centuries, Hangul was stigmatized as the “women’s script.” Only during and after Japanese colonization (1910–1945) did it become a rallying symbol of Korean identity. Post-independence, South Korea fully standardized Hangul in schools, laws, and media.

The result? Skyrocketing literacy, civic participation, and cultural confidence. Hangul wasn’t just a writing system. It was a nation-building technology.

Turkey: Break with the Past, Build the Future

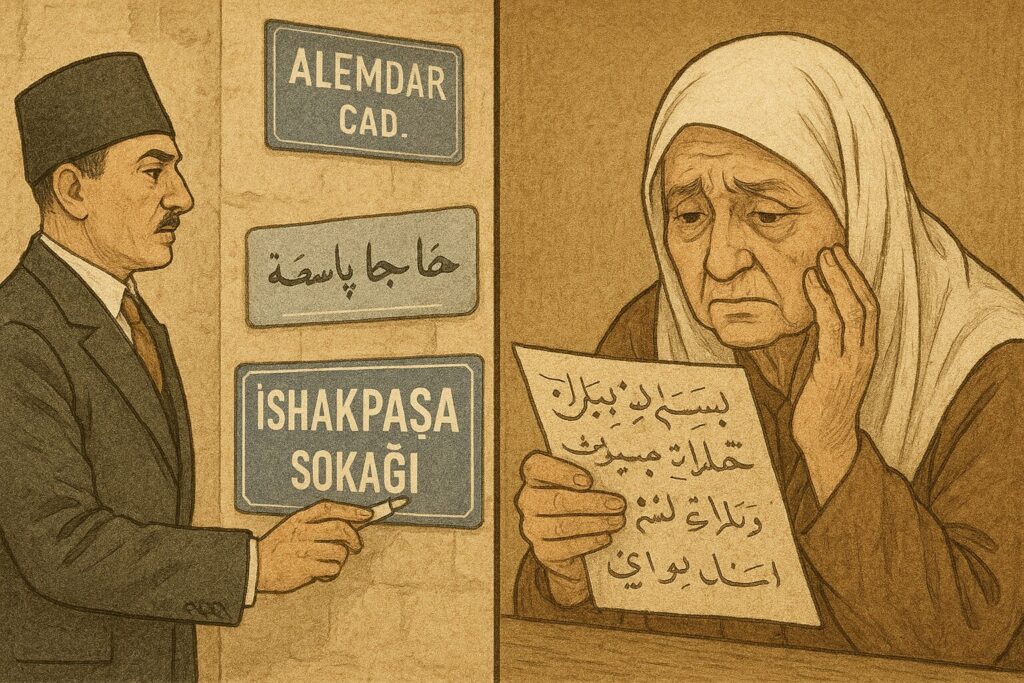

In 1928, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk did something even more radical: he abolished the Arabic-based Ottoman script and replaced it with a Latin alphabet. Overnight, street signs, textbooks, newspapers—all rewritten.

The move wasn’t just about easier spelling. It was part of a sweeping project to modernize, secularize, and Westernize Turkey.

And it worked. Literacy doubled in a decade. A new national identity emerged. But something was lost: millions of Turks could no longer read their own grandparents’ letters.

Why the U.S. Never Needed a Script Revolution

America never needed a language revolution because it built language infrastructure into its institutions from the start.

Horace Mann’s common schools. Standardized testing. Broadcast media. Immigration forms. All in English. Not because of a decree—but because of default.

It was a soft power strategy: make English the path to opportunity, and people will choose it.

What We Can Learn

The lesson from Seoul and Ankara isn’t that we should replace our language or script. It’s that language policies work best when they align with civic values and shared purpose.

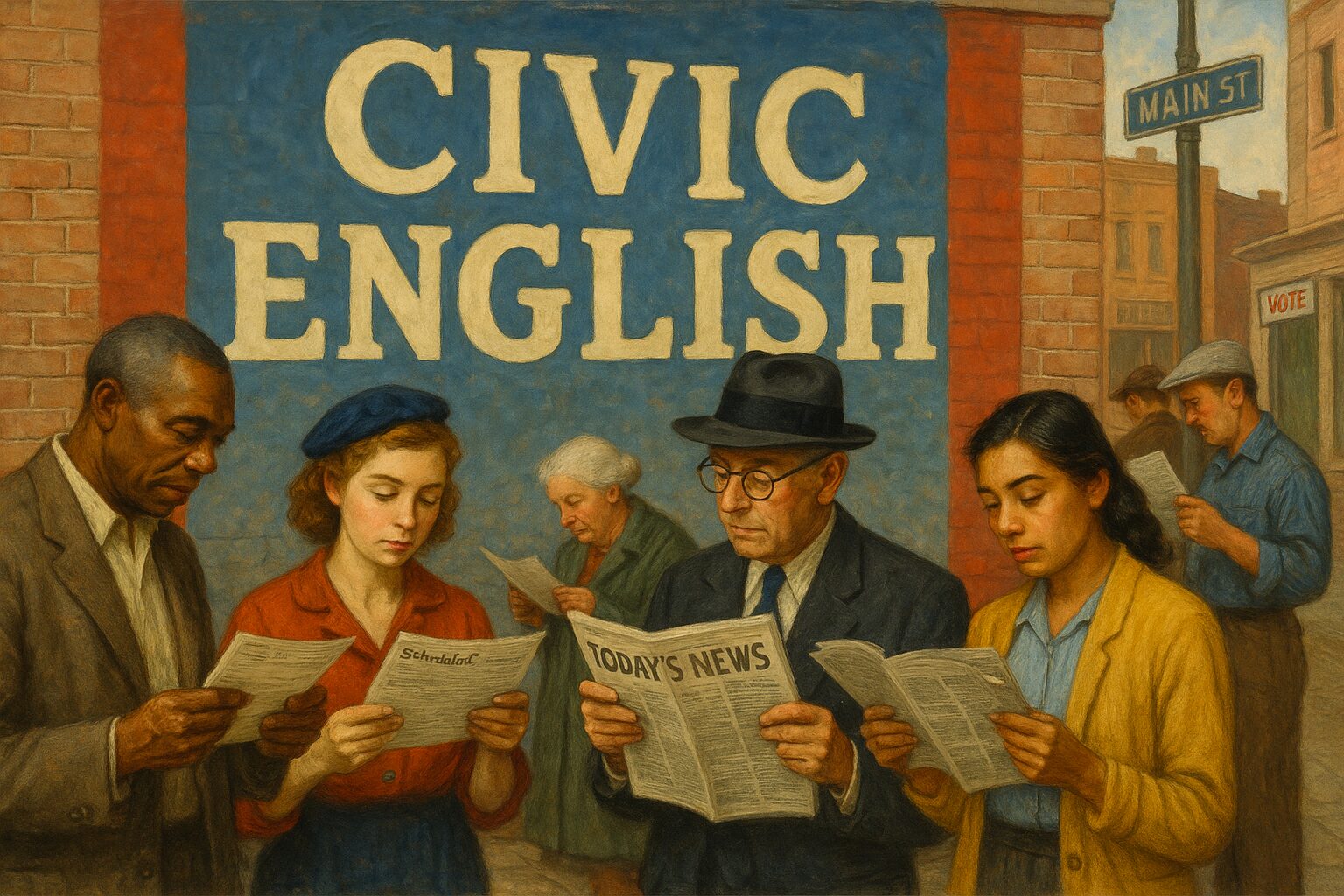

In America, English became the civic lingua franca not because it was mandated, but because it was useful. Inclusive. Empowering. That’s the model we should preserve.

So rather than legislate English as the official language, let’s:

- Fund civic English education (for native and non-native speakers alike)

- Train public officials to communicate clearly and accessibly

- Design forms, ballots, and media that teach as much as they inform

We don’t need to impose. We just need to architect.

Because in a democracy, the most powerful protocol is the one people choose to speak.

Author’s Note:

This post was written with help from ChatGPT, who served as my research assistant, draft whisperer, and occasional devil’s advocate. While I supplied the brainwaves, it handled the caffeine-free typing. Any errors are mine. Any unusually clever metaphors probably aren’t.