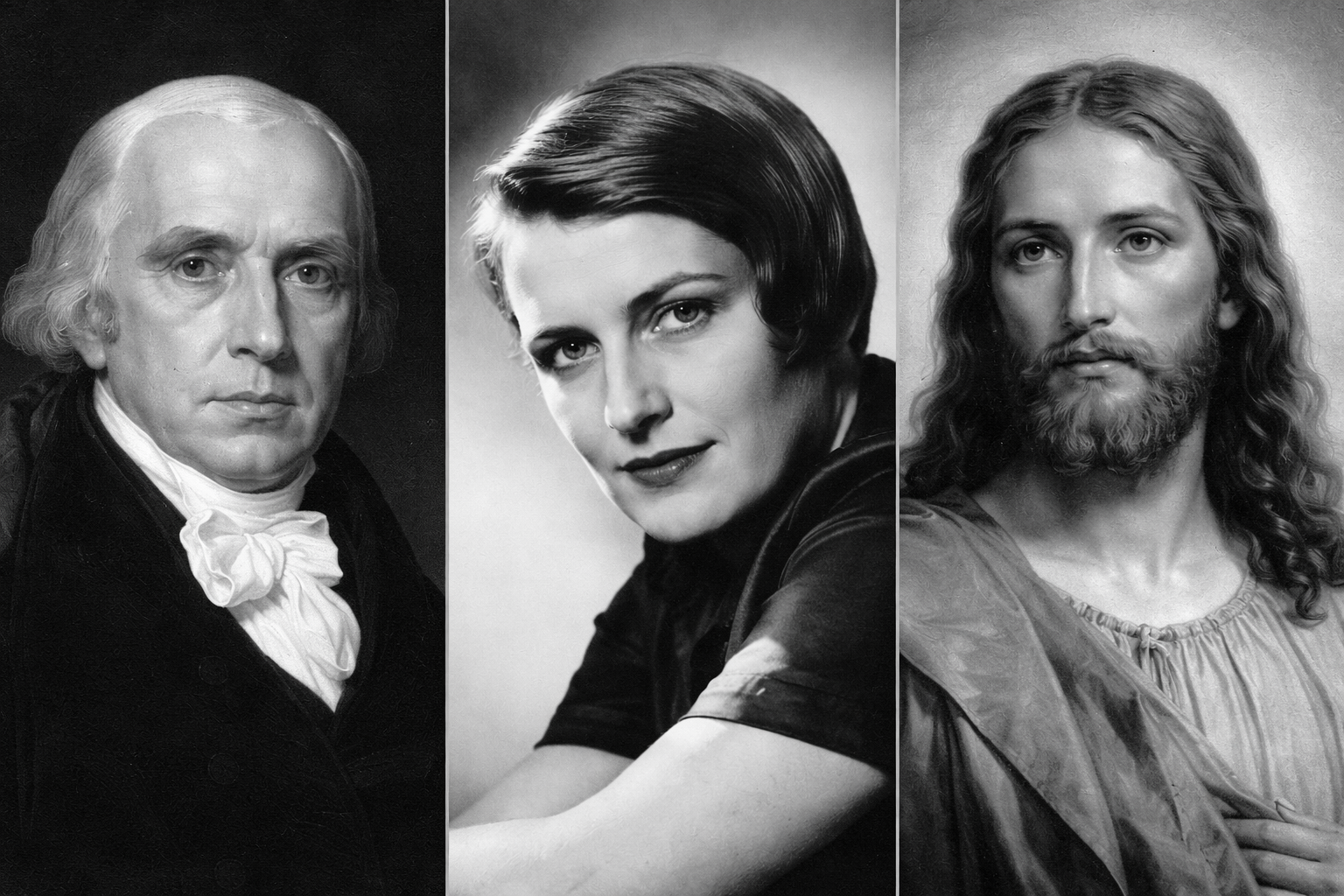

Three traditions, one problem: how societies cope with imperfect human beings

Modern political arguments often collapse into a single moral question: Can society rely on people to do the right thing? Behind debates over markets, government, and culture lies a deeper disagreement about human nature itself—specifically, about altruism. Are human beings naturally capable of self-sacrifice for the common good, or must institutions be designed to compensate for its absence?

Western civilization has offered at least three durable answers to that question. Each anchors a different domain of social life. Together, they form a three-legged stool upon which the modern American order still rests.

The first answer is institutional. James Madison assumed that altruism could not be relied upon at scale. In Federalist No. 10 and throughout the constitutional design, Madison treated virtue as desirable but scarce. The Constitution does not ask citizens or leaders to be angels. Instead, it channels ambition against ambition. Power checks power. Factions compete. Delay and friction replace moral trust. In this framework, good outcomes emerge not because people act selflessly, but because institutions mimic the stabilizing effects of altruism through structure. Madison’s republic substitutes constraint for virtue.

The second answer is economic. Ayn Rand rejected altruism not merely as unreliable, but as destructive. In her moral universe, self-sacrifice corrodes excellence and distorts incentives. Markets work precisely because they do not require people to act for others. Voluntary exchange aligns self-interest with productivity. Value is created when individuals pursue their own rational ends, not when they subordinate themselves to collective demands. Where Madison built guardrails around ambition, Rand liberated it. Markets succeed not by cultivating altruism, but by rendering it unnecessary.

The third answer lies outside politics and economics altogether. Jesus of Nazareth placed his faith almost entirely in altruism itself. His teachings call for radical self-sacrifice, moral transformation, and love unmediated by institutions. The Sermon on the Mount offers no blueprint for governance and little guidance for commerce. Instead, it demands a reordering of the soul. Turn the other cheek. Love enemies. Give without expectation of return. Jesus expressed little confidence in either government or markets as engines of moral good. His vision assumes that genuine justice emerges only when hearts are transformed.

These three answers do not compete on the same terrain. Madison governs politics. Rand governs markets. Jesus governs conscience. Each addresses the problem of human nature from a different angle, and each compensates for the failures of the others.

From Madison, we inherit a structure for disagreement when altruism fails. From Rand, we learn how competition and exchange function when altruism introduces fragility rather than strength. From Jesus, we learn the indispensable role of altruism within the individual soul. None can do the work of the others.

Trouble begins when one domain attempts to swallow the rest.

When politics demands moral purity, it collapses under faction and zeal. Madison warned against systems that assume virtue, because disappointment breeds instability. Revolutionary governments that expect citizens to behave like saints often discover—too late—that disappointment turns punitive. The guillotine is never far behind the sermon.

When markets are treated as moral teachers rather than coordination mechanisms, inequality acquires a moral gloss. Rand’s framework excels at generating wealth, but it offers little language for mercy, obligation, or restraint beyond contract. Market logic alone cannot answer questions of dignity or care for those who fail.

When religious altruism is imposed through law or commerce, it loses its voluntary character. Coerced virtue is no virtue at all. Jesus’s command to love cannot be legislated without becoming its opposite.

The American experiment has endured because it never fully resolved these tensions. Instead, it balanced them. The Constitution assumes flawed people. Markets harness self-interest. Religious and moral traditions cultivate virtue where institutions cannot reach. Each leg of the stool remains incomplete on its own.

In individual lives, one leg may rightly matter more than the others. Some lean toward faith, others toward markets, others toward institutional order. The strength of the American republic lies not in enforcing uniform balance, but in refusing to deny any leg its rightful place in the shared civic structure.

Let me be clear. This argument does not assert a moral equivalence among Jesus, Rand, and Madison. If that is the takeaway, the reader has missed the point. These figures operate in different domains, address different questions, and make fundamentally different claims. Jesus himself recognized this separation when he admonished his followers to render unto Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and unto God what belongs to God. His moral vision does not collapse into governance or commerce. Madison offers institutional architecture. Rand offers an economic ethic. The comparison is structural, not ethical. It concerns how societies function, not how souls are judged.

This balance also explains why periods of crisis feel so disorienting. When trust in institutions erodes, citizens ask politics to supply morality. When markets feel unjust, they are asked to deliver fairness. When culture frays, religion is asked to restore order through power rather than persuasion. Each substitution fails, because each domain answers a different question.

Madison asks how power can be restrained without relying on virtue. Rand asks how prosperity can be created without demanding sacrifice. Jesus asks how human beings ought to live, regardless of outcomes. None offers a complete theory of society. Together, they outline its limits.

The enduring challenge is not to choose among them, but to remember why all three remain necessary. Politics cannot save souls. Markets cannot teach love. Religion cannot replace institutions. Enlightenment lies in holding these answers in tension—accepting that human nature requires structure, incentive, and moral aspiration, each in its proper place.

Compromise is never easy. It never has been. Civilizations that forget the limits of altruism—or its necessity—rarely endure.

Disclaimer: Drafted by a human. Polished with the help of ChatGPT, which supplied no opinions, held no beliefs, and accepted no moral responsibility.